Relying on Chinese language sources, this essay attempts to outline such a history. In this essay, I make three interrelated arguments. First, I argue that due to gaps in the canonical prescriptions on mourning, there was some ambiguity about how properly to bury children who died under the age of eight sui.[1] As a result, it appears that many children were buried, if at all, with minimal effort. Second, I argue that this began to change in the eighteenth century as Qing officials in the northern provinces of Shaanxi and Shanxi began a campaign against the exposure of child corpses.

I show that these campaigns began in northern China in the early eighteenth century and spread to the Lower Yangzi region, where they became a cornerstone of elite philanthropic activity by the mid-nineteenth century. Finally, I argue that what came to be known in the West as the “baby tower” was likely a localized, and relatively recent, solution to the problem of infant burial in the region around Shanghai.

Infant Burial in Western Discourse

In 1853, the peripatetic author Bayard Taylor visited the northern outskirts of Shanghai, accompanied by two American missionaries. Taylor described the following scene after passing by a large cemetery:

Between the graves and the city wall stands a low building, in a clump of cedar trees. This is one of the “Baby Towers,” of which there are several near the city. All infants who die under the age of one year are not honored with burial, but done up in a package, with matting and cords, and thrown into the tower, or rather well, as it is sunk some distance below the earth. The top, which rises about ten feet above the ground, is roofed, but an aperture is left for casting in the bodies. Looking into it, we see that the tower is filled nearly to the roof with bundles of matting, from which exhales a pestilent effluvium.[2]

Figure 1. Shanghai Baby Tower. John Scarth, Twelve Years in China, (Edinburgh: Thomas Constable, 1860), 103.

Taylor’s account of these depositories was one of the first of what would eventually become a voluminous literature representing so-called “baby towers” to Western readers. For nearly a century afterward, observers of China frequently felt compelled to proffer their remarks on the burial practices of young children.

Many commentators, some of whom had never even seen the structures, made little attempt to conceal their feelings of revulsion toward these depositories, which they considered to be malodorous killing grounds. Another early reference, by George W. Cooke in 1858, set the tone for many of the reports that would follow. While touring Shanghai with British Vice-Consul Frederick Harvey, Cooke recalled the following exchange.

Undismayed, the energetic vice-consul, who sometimes acts as guide, philosopher, and friend, and expatiates with me over this maze. Advances through a vapour so thick that I wonder the Chinese do not cut it into blocks and use it for manure; and at a distance of five yards from the building puffed hard at his cheroot, and said, –

“That is the Baby-tower.”

“The —?” said I, inquiringly.

“The Baby-tower. Look through that rent in the stonework – not too close, or the stream of effluvia may kill you. You see a mound of whisps of bamboo straw. It seems to move, but it is only the crawling of the worms. Sometimes a tiny leg or arm, or a little fleshless bone, protrudes from the straw. The tower is not so full now as I have seen it; they must have cleared it out recently.”

“Is this a cemetery or a slaughterhouse?”

“The Chinese say it is only a tomb. Coffins are dear, and the peasantry are poor. When a child dies, the parents wrap it round with bamboo, throw it in at that window, and all is done. When the tower is full, the proper authorities burn the heap, and spread the ashes over the land.”

There is no inquiry, no check. The parent has power to kill or to save. Nature speaks in the heart of a Chinese mother as in the breast of an English matron. But want and shame sometimes shout louder still.[3]

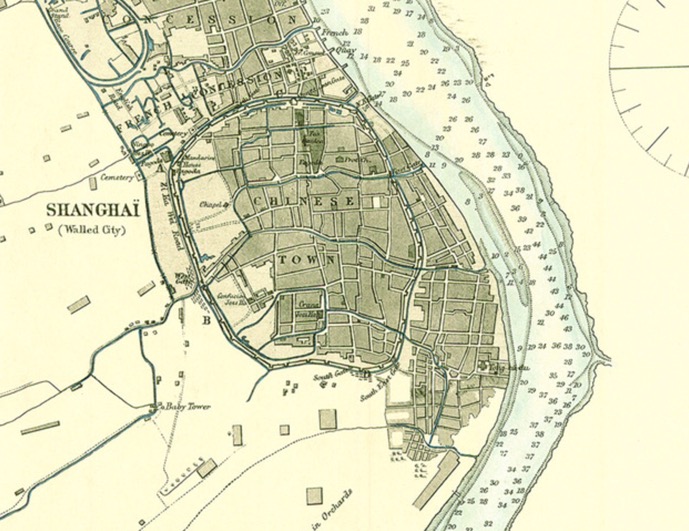

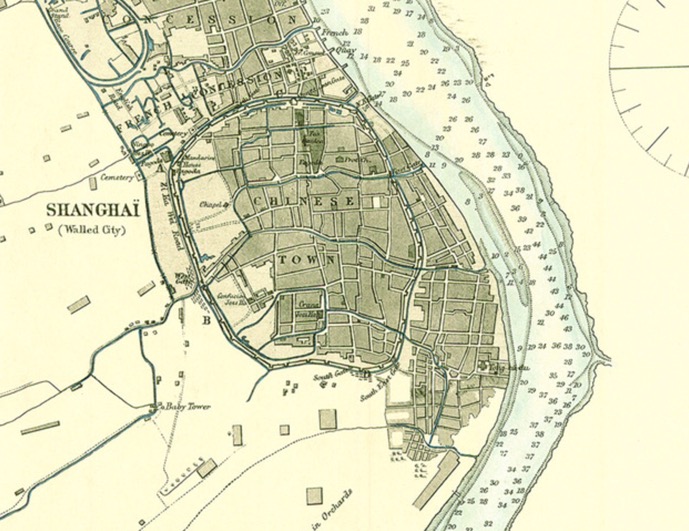

Figure 2. “Shanghai and Its Environs, 1862.” Notice the “baby tower” located just to the southwest of the walled Chinese city. United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO).

One of the earlier reports of baby towers, this account, and others that followed, introduced one of the most vexing questions about these structures for Western audiences: Did baby towers receive the bodies of dead children or living ones? Undoubtedly, Cooke’s audience found his query as to whether the building was a cemetery or a slaughterhouse both horrifying and titillating, as it raised the possibility that baby towers were associated with one of the institutions foreigners found most outrageous in China, that of female infanticide. Scores of articles from the period made similar suggestions, insinuating that whenever the bodies of young girls were deposited into the towers, “the parents are not always particular to ascertain if it is quite dead or not.”[4] Other writers were far less circumspect, stating quite plainly that the baby tower was a “frightful murder-house,” and children “were thrown alive into this ghastly receptacle, and left to die at their leisure on the heaps of putrid bodies below.”[5]

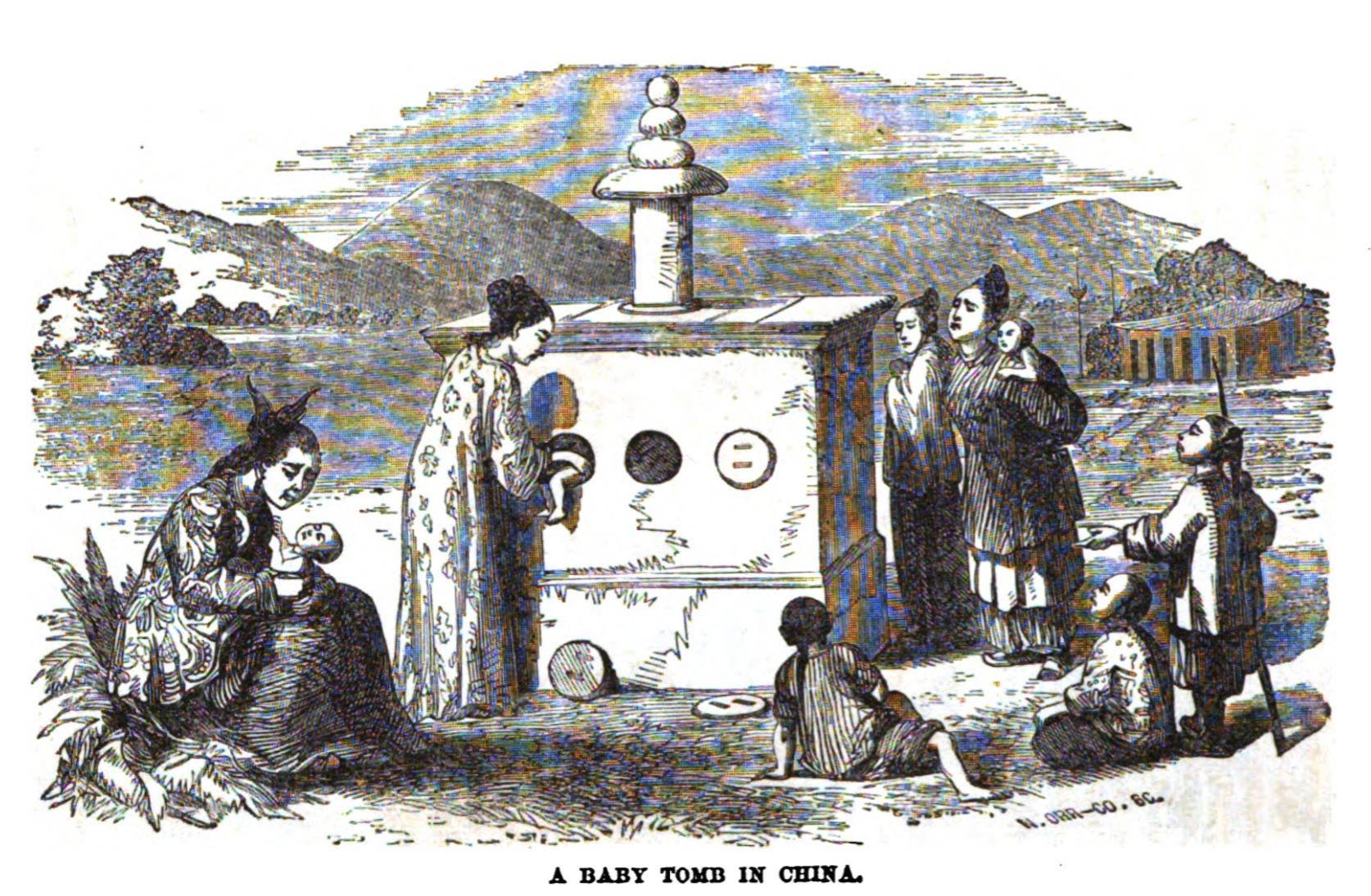

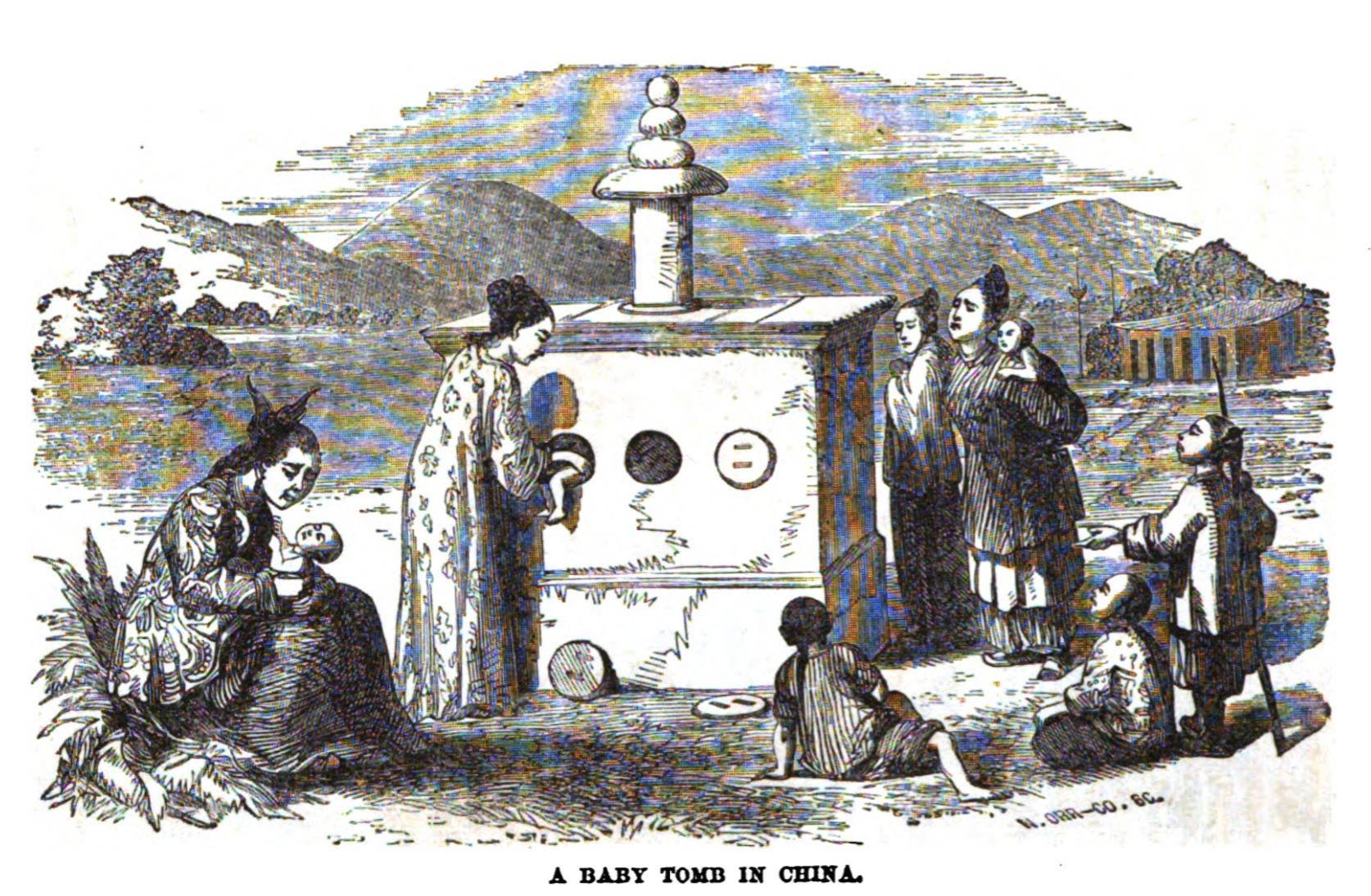

Figure 3. “A Baby Tomb in China.” Ballou’s Monthly Magazine (January-June 1870), 109.

Although their original purpose was never entirely lost, for most readers baby towers were less about burying infants than about killing them. Considered in this light, the baby tower was interpreted by foreigners as a monument to Chinese people’s cruelty toward children and their disregard for human life more broadly. As a result, these buildings were to become yet another piece of evidence to support the persistent trope that Chinese people are baby killers.[6]

Due to their link with infanticide, baby towers would forever be connected in many people’s minds with reproduction and its control, rather than with Chinese burial customs.[7] This essay is an attempt to situate baby towers within the broader context of infant burial practices in late imperial China.

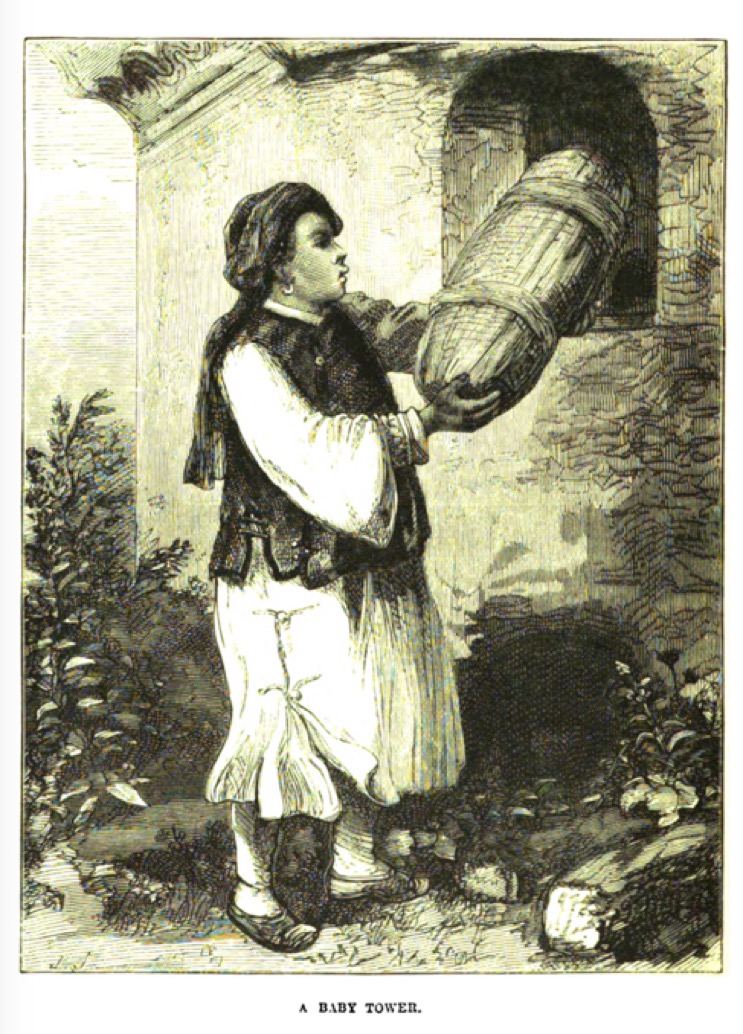

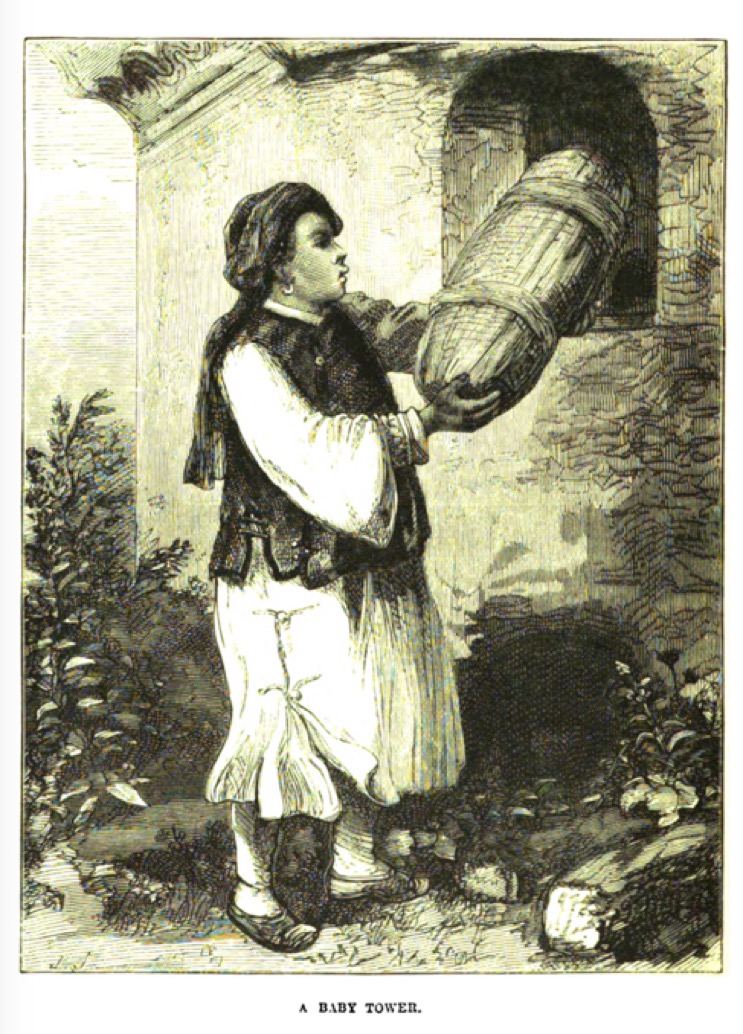

Figure 4. “A Baby Tower.” Mary Bryson, Child Life in Chinese Homes (London: Religious Tract Society, 1885), 16.

Mourning the Infant Dead

In reading through the historical sources, there is one sobering fact that is indisputable: there was a surfeit of dead infants in late imperial China.[8] We know, for example, that even in the best of circumstances, infant mortality was extremely high.[9] Even the Qianlong Emperor, who was certainly more able than most to secure the health of his offspring, would see only eight of his twenty-seven children survive into their thirties; ten of them died before the age of five.[10] Considering this grim state of affairs, the question naturally arose as to what to do with the proliferation of infant corpses.

Historically, infants in China did not receive burial honors. Classical texts such as the Yili 儀禮 outlined mourning practices for those who died an “early death” (shang 殤). An early death was defined as any death that took place between the ages of eight sui and nineteen sui, as long as the deceased had not gone through the capping or pinning ceremonies and was not yet betrothed. The original text of the Yili divides premature deaths into three categories: zhangshang 長殤, “upper early deaths,” for those who died between the ages of sixteen and nineteen; zhongshang 中殤, “middle early deaths,” for those who perished between the ages of twelve and fifteen; and xiashang 下殤, “lower early deaths,” for those who died between the ages of eight and eleven. For each gradation of premature death, different mourning clothes were prescribed. The status of children who died before reaching the age of eight sui was ambiguous. Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (127–200), who wrote one of the earliest and most influential commentaries on the Yili, specified that those who died before the age of eight “had no [mourning] clothes” worn for them and were “only wailed for.”[11] Zheng wrote that one day of wailing was permitted for each month the child had been alive. In other words, a child who had lived for twenty-six months could receive twenty-six days of wailing. A subsequent commentary on the Yili by Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200) further explained, “Three months after a child is born, the father names it, so [if the child dies after then], it can be wailed for. However, if it does not yet have a name, then there should be no wailing.”[12] These provisions also found their way into Zhu Xi’s Jiali (家禮), or Family Rituals, which served as the most important text for specifying mourning practices during the later imperial period.[13]

In the Bellies of Beasts and Birds

Despite these specifications for mourning, classical texts provided parents with little guidance about how to bury children who died before the age of eight sui. Indeed, families appeared to have little direction in this regard, save for the pull of local custom. As a result, burial customs for children differed considerably, depending on a family’s native place and socioeconomic status. In general, most young children seem to have been buried with minimal effort, if at all. As the historian Susan Naquin has written, “When infants died, the bodies could be buried perfunctorily in shallow graves or simply abandoned. The older the child, the more elaborate the ceremony. Within private graveyards, certain (less desirable) areas were apparently reserved for infants and children.”[14] Perfunctory burial or abandonment appears to have been nearly universal during the Qing. About the burial of children in the region around Xiamen during the late Qing, J. J. M. de Groot wrote,

The corpse is buried anywhere at a depth of a few inches, and the rest of the earth heaped up over it. Within a short time the dust returns to dust, or, as is very often the case, the remains are devoured by dogs and crows. No property in the ground is secured, nor is any attention paid to the spot afterwards. Many babies are not buried at all, the urn or box being merely set aside in the open country, where it likewise soon falls a prey to birds and starving dogs.[15]

Elsewhere, he characterized the burial of children as a “systematic throwing away.” He lamented, “Countless are the babes that, closed in urns or wooden boxes, are abandoned in the open country and so given a prey to ravens, dogs and swine, or to quick dissolution under the operation of weather and vermin.”[16] De Groot’s observations are corroborated in Chinese language sources and suggest that burial practices in the Qing conformed to broader patterns of infant burial worldwide. Indeed, the anthropologist David Lancy has argued that because of their liminality and incompleteness, “babies aren’t persons,” observing that in many civilizations around the world, “burial rites and mourning may be minimal or actively discouraged in the case of a child younger than five years, or even as late as ten.”[17]

What is interesting about perfunctory burial or abandonment—what I will call corpse “exposure”—is that there is evidence that this was one of the preferred ways to dispose of infant corpses in Qing China, at least among the poorer classes. During the Yongzheng reign, the head of the department of Shuozhou 朔州, Shanxi, Wang Sisheng 汪嗣聖, issued a proclamation prohibiting the people in his jurisdiction from exposing the bodies of children who had died before the age of eight, suggesting they be buried instead. He opened his proclamation by arguing that burying infants reflects the way of Heaven and the natural affection between parents and children. “Parents celebrate upon birth,” wrote Wang, “and they bury upon death.” He then proceeded to quote the prescriptions contained in the Family Rituals described above, regarding the commemoration of early deaths. Recognizing, perhaps, that this text did not supply the necessary clarification he sought, he turned to one of the classics, the Liji 禮記, or Record of Rites. Wang wrote,

As it is recorded in the “Tan Gong” [portion of the Liji]: The people of Zhou buried those who died between 16 and 19 in the coffins of Yin; those who died between 12 and 15 or between 8 and 11 in the brick enclosures of Xia; and those who died (still younger), for whom no mourning is worn, in the earthenware enclosures of the time of the lord of Yu.[18]

Wang concluded, “Although the death of infants does not require the same mourning as adults, since the [custom] of preparing the coffin and returning it to the earth comes from previous generations, it should not be altered.”[19] Elsewhere in his proclamation, Wang again turned to the Liji to relate a story about Confucius, whose pet dog had recently died. Before instructing his student Zigong bury the dog, Confucius reportedly said, “I have heard that a worn-out curtain should not be thrown away, but may be used to bury a horse in; and that a worn-out umbrella should not be thrown away, but may be used to bury a dog in.” Wang continued, “Confucius’ dog died, [and he said]: ‘In putting the dog into the grave, you can use my mat; and do not let its head get buried in the earth.’ So when something we clutch to our bosoms suddenly dies, how can we allow it to be exposed in a way that does not match the level of care shown even dogs and horses?”[20]

The problem, as Wang noted in his proclamation, was that “stupid people” (yumeng 愚氓) in his jurisdiction followed the “evil custom” of abandoning infant corpses in the wilds with neither a coffin nor a proper burial: “their skulls sucked to the howling of foxes, their bellies filled by the pecking of birds.” One of Wang’s colleagues, Liu Shiming 劉士銘, wrote about the same problem in a proclamation he issued in Shuoping Prefecture to “collect and bury the remains of infants.” Liu was the prefect within which Wang’s jurisdiction of Shuozhou was located, so the two undoubtedly communicated with one another about this issue. He wrote that he had heard about an “ugly practice” in the Shuo region. “Whenever a birth ends in the premature death of an infant,” Liu wrote, “regardless of whether it is male or female, it is always discarded in an open field, exposed to the wind and sun, and entrusted to the dogs and wolves to eat.”[21] It was this last eventuality that many writers clearly found to be most worrisome. The revulsion Ji Shilin 姬士麟, an official who was from Gaoping 高平 County, Shanxi, felt at the possibility that one’s progeny would be consumed by wild beasts is unmistakable. In an essay he penned entitled “An Exhortation to Bury Infants,” Ji says that although infants have not yet grown into adults, they are alive, and they are the “bones and blood” (guxue 骨血) of their parents. Likewise, the bones and blood of the parents have been transmitted from the bones and blood of their ancestors. Ji cries, “Do you really want your own bones and blood to be buried in the bellies of beasts and birds? What sorrow! Your body, hair, and skin were all received from your parents, so you dare not do them harm. As for harming them, is it not unfilial to take the bones and blood of your ancestors and bury them in the bellies of beasts and birds? What cruelty!”[22]

The use of animals as rhetorical devices appears elsewhere in East Asian discussions of dead children. In his work on Japanese infanticide, Fabian Drixler has argued that animals frequently served as “moral guideposts” in literature denouncing infanticide: “Animals played a useful multivalent role in the effort of the propagandists; indicating on the one hand the natural order of things, they could also remind humans that they were obliged to do better than beings that occupied a lower rung of existence.”[23] We see something similar here, as dogs appear both as worthy objects of burial (in the case of Confucius) yet unworthy destinations for burial (in the case of infant exposure). Likewise, animals are invoked, paradoxically, as possessing an innate supra-human desire to care for their young, while at the same time being represented as the height of beastliness. As an official from Zhaocheng 趙城, Shanxi, wrote in an essay against infant exposure, “Record of Burying the Early Dead” 埋殤記,

How in the world could heavenly principles be corrupted and the human heart be forsaken like this? Even birds are able to feed their fledglings by mouth; and tigers and wolves do not eat their own young. But when my own flesh and bones encounters misfortune, cannot get better, and then reaches the point of death, it is cast out of the bosom to the sound of its own weeping. It is preposterous to say that those whom you have caressed and dearly loved—who now desire only to be enveloped in the grave—instead should fill the bellies of birds, foxes, dogs, and pigs.[24]

The implication, of course, was that those who exposed children were themselves sub-bestial, less compassionate than even birds, tigers, and wolves. In these commentaries, the aural and gustatory senses played a key role in conjuring the inhumane. Writers asked the reader to picture himself, his immediate family, and his ancestors being eviscerated and consumed by wild animals, and to imagine the sucking, pecking, and gnawing that would necessarily accompany such a calamity.

Life-Stealing Demons and Evil Spawn

Even though these officials expressed in the most vivid terms their shock and horror with the practice, there were evidently quite a few “stupid people” who were exposing their infant dead. These official appeals reveal that, rather than being evidence of neglect, exposing corpses was an intentional burial strategy adopted by common people, especially in northern China. For instance, the gazetteer of Fenyang 汾陽 County, Shanxi, stated that infants were not buried because they were thought to damage the fengshui of ancestral tombs.[25] Ji Shilin, on the other hand, traces the practice of exposing infant corpses in Shanxi to two taboos that were apparently deeply entrenched in the area. One stipulated that burying an infant would make a couple infertile:

There is a taboo that says if you bury an infant then you will never again have children in the future. Alas, this is how deep the stupidity is. As for burying a dead infant and never again giving birth, can it really be that an infant has the ability (ling 靈) to control whether its parents will not give birth, to the point that the joy of an infant is suppressed and brutal violence inflicted on its body?

The other taboo stated that it was profane: “There is another taboo that says burying infants is ‘bu dang’ 不當. ‘Bu dang’ is a local expression. It means that one has offended the gods and spirits.”[26]

People ostensibly exposed infants in order to minimize the negative influences that flowed to the household.

Indeed, many reports about infant exposure emphasized the deeply held belief that exposing infants would convey benefits to either the dead child or its family. Wang Sisheng suggested that people in his area (Shuozhou, Shanxi) exposed corpses because they believed that dead infants, if left unburied, went straight to paradise: “The local people’s idiotic reasoning is that [they think] upon death [the infant] goes immediately to heaven, while avoiding a descent into the underworld. I do not know who fabricated this theory or when it began, but generations have tried to eliminate it without success because the delusion is so deep.”[27] Many of their concerns reportedly revolved around reincarnation. People were either concerned that their dead offspring would not be reincarnated, or reincarnated in an undesirable location—specifically, back to the family whence they came. For example, according to the "local customs” (fengsu 風俗) section of the Yongping 永平 prefectural gazetteer, parents did not fear the loss of a child as much as they did the prospect that it might linger after death:

There are no parents that do not cherish their children, from nurturing them at birth to mourning them at death. Yet it is a Yongping custom that when children die in infancy (yaoshang 夭殤), [parents] give no thought to accumulating merit and waiting for the next birth. They do not lay them out in coffins, but rather discard and expose [their corpses]. They are so worried that [the children] will be reincarnated back to the mother’s womb (futou mutai 復投母胎) that in their excessive sorrow they become more merciless than even jackals and tigers. The late Prefect Zhang Chaocong 張朝琮 [fl. 1707] issued a notice prohibiting this custom in order to reduce its prevalence. Those who have the responsibility of protecting newborns should follow suit in order to eradicate [the custom] permanently. This is the meaning of showing kindness to the dead (zeji kugu zhi yi 澤及枯骨之意).[28]

As this passage suggests, the reason that infant corpses were exposed was precisely so the child would not remain in the family. Exposure was a method that ensured that once a child died, the family would be rid of it forever.

Indeed, what parents seemed to fear most was the “return” or “coming back” (fulai 復來, zailai 再來) of a dead child. The reasons for this were twofold. On the one hand, dead children who “came back” were thought to be short-lived, bringing back with them whatever ailment had led to their deaths in the first place, which imperiled a family’s fertility. On the other hand, the returned child would pose a threat to the family if it sought to harm it in some way. The same official in Zhaocheng, Shanxi, mentioned above wrote about these anxieties:

One time when I was out riding alone outside the east gate, I went into a walled village and saw an old mother clutching a cloth bag. In a panic, she ran out of a small grove of trees. I grilled her about what she was doing, but she didn’t respond. My squire told me that this was a dead child, which she intended to discard in a ditch. I despondently said, “The children die and they’re thrown into ditches!?” Apparently, Shanxi has a custom where children under the age of six and seven sui, no matter how they fall ill and die, are all abandoned because [parents] are afraid that they will immediately “come back” (fulai 復來).[29]

It is not evident in this particular account what was meant by the term “coming back,” but this was a phrase that was used in one form or another in multiple sources from northern China. From these texts, it becomes clear that coming back referred to visitations of one kind or another, where the dead infant returned to the household to cause the death of a subsequent child, or to exact revenge on the family. The “local customs” section of the Wuyang 舞陽 County, Henan, gazetteer explained the phenomenon in the following way:

When children die young, it is appropriate to bury them and return their bodies to the soil. This is the desire of parents. Yet there is a category of stupid people who give birth to a boy or a girl, and when it gets sick and dies, they call it a “life-stealing demon” (toushenggui 偷生鬼). They take its corpse and cruelly discard it on the outskirts of town to fill the bellies of wolves and dogs. It is said that by doing this they can prevent [the child] from coming back (zailai) in another pregnancy. Moreover, when a firstborn son or daughter falls ill and dies, they must be discarded and not buried. It is said that by doing so later births will enjoy a long life. To harbor these kinds of intentions truly is barbaric.[30]

The phrase “life-stealing demon” appears to be a local expression in Henan Province for the returned infant. The gazetteer from Yiyang 伊陽 County, Henan, states, “According to custom, all boys and girls who die between the ages of birth and six or seven sui are called ‘life-stealing demons’ (toushenggui), and there is a fear that once they have died, they will come back (fulai). So, they are bundled in reed mats and laid in a ditch for the birds, jackals, and dogs to cruelly eat.”[31]

A similar phenomenon is expressed in a slightly different way in sources from Shaanxi, which report that dead infants were feared to be “evil spawn” (niezhong 孽種) whose powers could be neutralized though exposure. In a proclamation to ban the exposure of children, Wang Chongli 王崇禮 (fl. 1750), the magistrate of Yanchang 延長 County, Shaanxi, wrote:

When considering the birth of boys and girls, who does not hope that they mature completely? But if their lot in life is bad or they die early, this is not their fault. After inquiring, I discovered that the common people of Yanchang are confused about the doctrine of reincarnation. They say that when a child (xiao’er 小兒) dies, it is an evil spawn (niezhong 孽種). If the child is not deposited in a deep ditch, it causes the child to decay prematurely, so it will be reincarnated back again (bi zailai toutai 必再來投胎), whereupon the parents will suffer harm.[32]

The American Presbyterian Missionary Michael Simpson Culbertson encountered similar ideas in Ningbo, where he was stationed in the mid-nineteenth century. Culbertson details some of the measures parents took to protect themselves upon the death of a child, including setting off fireworks in the home and hiring a Daoist exorcist to “sweep away” its evil spirit. According to Culbertson, it was believed that when a child died, it indicated that the child was actually a spirit that had been born to the parents to seek revenge for some past injustice. Culbertson explained, “It was for some such purpose as this that the child came into this world, and quartered itself upon the parents, subjecting them to much trouble and expense, and then leaving them before reaching an age at which its services could, in any measure, repay them for their pains. This is the view taken, when a child dies under the age of sixteen, and the fear is that it may again be born, for a similar purpose, as the child of the same parents.” The Qing official and author, Ji Yun 紀昀 (1724–1805), who hailed from Xian 獻 County, Hebei Province, claimed these children were the product of wandering ghosts: “Exceptionally, there may be stray souls who attach themselves to women who become pregnant: This is called ‘stealing life.’”[33]

According to these descriptions, wild animals played a crucial role in eliminating the possibility that a child might return. The sources do not say precisely how or why this happened, but it may have had something to do with the dismemberment and consumption that naturally accompanied exposure. For example, Wang Qingren 王清任 (1768–1831), a Qing dynasty physician, was traveling through Luanzhou 滦州 Prefecture, Zhili, during an epidemic that killed “eight or nine out of every ten children.” Wang wrote, “Poor families mostly used substitution mats to wrap and bury [the dead]. Substitution mats are mats that replace coffins. It was the local custom to bury shallowly, with the intention that dogs would eat [the bodies. This would] have the benefit [of ensuring] the next child did not die (更不深埋,意在犬食, 利於下胎不死). Because of this, every day in each charitable graveyard, there were over a hundred children with torn abdomens exposing their viscera.”[34] According to Wang’s testimony, consumption by animals played a key role in preventing children from returning to the family. The likely explanation is that consumption destroyed the somatic integrity of the corpse, which prevented successful reincarnation. In the popular Buddhist imagination, the dead body “could not enter purgatory and go through the process of paying off his karmic debt that would allow his rebirth if his body were in pieces.”[35] Thus, the disarticulated infant corpse was stranded in an existential no-man’s land.

Parents could also mutilate an infant’s corpse to thwart its return. The biography of Wang Qingliang 王清亮 in the Qingpu 青浦 County gazetteer describes his time an assistant magistrate (dianshi 典史) in Nanyang 南陽 County, Henan, during the nineteenth century and his response to the local custom of infant exposure:

Nanyang has a custom that as soon as a child (youhai 幼孩) dies the parents take a knife and hack it up (zhuozhi 斫之). It is said they fear it will come again to demand retribution (suozhai 索債). Qingliang requested that the magistrate strictly prohibit this custom, so the corpses of discarded children were collected and placed in a cemetery for burial.[36]

We read something similar in the writings of Ji Shilin (Gaoping, Shanxi) discussed above, where he says that some parents who had suffered through the deaths of multiple children would mutilate their children before laying them out: “Because their boys and girls do not survive, we see some people who repeatedly have births and deaths. They cut off [the child’s] ear or sever a finger because they believe that [if they do], this child will not come again (zailai 再來), but will be reincarnated, and the next birth will live.”[37] Henrietta Harrison has written that infants in southern Shanxi were mutilated, or marked with soot and ink, so they could be identified by parents if they were ever to return later.[38] A more likely explanation is that mutilation served an exorcistic purpose, as the malignant spirit was violently expelled from the household. Donald Harper has detailed similarly violent practices in early China to dispel evil newborn spirits, and we have evidence that such practices persisted into the late twentieth century in Taiwan.[39]

Making Place for the Infant Dead

Needless to say, there was a difference of opinion as to whether or how dead babies should be buried. Many elites, such as those who compiled or contributed to local gazetteers, favored some form of interment for infant corpses. Other people, likely at the opposite end of the socioeconomic spectrum, appear to have favored either shallow burial or no burial at all. Not surprisingly, officials used their position in society to lobby strenuously to persuade people to bury their young. They did this not only by writing proclamations and essays of the type discussed above, but also by provided spaces for child corpses to be placed. Many of the officials discussed earlier promoted concrete measures to assist in the burial of the young. The most daunting obstacle, argued Liu Shiming, was that people could not be expected to bury their young if they had no money for coffins or land for gravesites. As a result, he reported that his prefecture (Shuoping) set aside land and provided coffins expressly for this purpose.[40] Burial efforts became a deeply personal campaign for some. For example, Ji Shilin described a visit to Pingyang 平陽, Shanxi, where as he traveled on the road, he saw hillsides dotted with little painted holes. He asked a local what they were, and was told they were places to bury wooden coffins that held the remains of infants. Ji was so inspired by this sight that he committed himself to making “several ten” coffins a year—“three chi long, no more than five fen thick, with small nails on all four sides”—that he would store in a public place so people could use them “without paying, without leaving their names, and without registering their households.” He encouraged all “benevolent gentlemen” to do the same.[41]

That Qing officials engaged in efforts of this kind comes as no surprise. From very early in Chinese history, officials and elites were encouraged to care for the public dead, and doing so enabled them to enact longstanding models of good governance, earn merit, and assert and justify their status in local society. For example, the Liji states that in the first month of spring, “Skeletons should be covered up, and bones with the flesh attached to them buried.”[42] Later generations of officials understood the collection and interment of exposed bones, upon which seasonal weather depended, as one of the key functions of government, and failure to do so was seen as a lapse of administration and one of the primary causes of drought.[43] During the late Ming dynasty, elites regularly provided land and coffins for abandoned corpses that belonged to poor families, or nobody at all.[44] This form of philanthropy appears to have accelerated during the Qing dynasty, as scholars such as Angela Leung have shown, but the imperative to do so was quite old.[45]

What was new was the increasing attention that burying children received as well as the particular forms this burial took. As early as the late seventeenth century, officials may have initiated burial efforts. For example, in 1689 Magistrate Hua Bin 滑彬 in Huixian County, Hebei, prohibited the exposure of infants and may have established a charitable graveyard for children, although this last point is unclear. Similar efforts were undertaken by an official named Wang Tiyuan 王體元 (fl. 1700), who penned an essay entitled “Advocating the Burial of Infants,” which discussed the problem of infant exposure in his native place of Pucheng 蒲城, Shaanxi. The essay was reportedly inscribed into a stone stele, but the text has since been lost. The earliest organized campaign to collect and bury infant corpses that I can find appears in 1706 (Kangxi 45). In that year, Fan Guangxi 范光曦 the magistrate of Linyou 麟遊 County, Shaanxi, submitted a memorial to his superiors, asking them to issue proclamations prohibiting the “Shaanxi custom” of exposing and abandoning infant corpses. Fan was moved by the same concerns mentioned above—exposure to the elements, qualms about corpses being eaten by animals, and so forth. In the end, he was able to persuade a host of other officials in Shaanxi to issue orders prohibiting corpse abandonment and ordering the burial of dead children in their jurisdictions, including the governor-general of Chuan-Shaan, Boji 愽濟; the Shaanxi governor, Ehai 鄂海; the lieutenant governor, Eluo 鄂洛; and the grain and salt intendant, Fu Zeyuan 傅澤淵.[46] Prior to this episode, child corpses simply did not receive as much attention in local histories. As we move into through the eighteenth century, other officials, especially in the northern provinces of Shanxi, Shaanxi, Zhili, and Shandong, initiated their own campaigns to bury dead children. We have already heard about the efforts of Zhang Chaocong in Yongping Prefecture (ca. 1707); but we also see burial campaigns in Fenyang 汾陽 County, Shanxi (ca. 1710), and Shuozhou and Shuoping (ca. 1730) early in the eighteenth century. This does not mean, of course, that infant corpses were not gathered during earlier periods as part of long-standing bone-collecting efforts, but I can find no evidence that infants existed as a special category of corpse in need of extraordinary protections prior to the early eighteenth century. A trend like this is admittedly difficult to quantify. Because we have more extant gazetteers from later periods, we naturally will find more references to infant burial the later we look. Thus, any conclusions about this pattern should be approached with caution. However, the evolution appears to be unmistakable.

The consideration paid to child corpses can be seen in the subsequent push in the mid-eighteenth century by Qing officials to establish “charitable graveyards” (yizhong 義塚) dedicated explicitly to the interment of infants. Donating burial land for the poor had long been a cornerstone of elite philanthropic activity, but efforts to establish separate burial grounds for children appear to have been rare before the Kangxi reign. The three Shanxi officials discussed earlier—Wang Sisheng, Liu Shiming, and Ji Shilin—all supported the creation of dedicated spaces for burying the young. Similar measures took place elsewhere in Shanxi. For example, Wang Chang 王錩 (fl. 1745), who served as magistrate of Xiaoyi 孝義 County, Shanxi, during the mid-Qianlong period, was moved by the bodies of dead children that lined the county’s roads. To combat this practice, he ordered that bricks be used to create cavities in the outer walls of the city, on both the north and south sides of the city. He then ordered that dead infants be placed in them, and he strictly forbade the discarding of infant corpses.[47] Similarly, Zhang Sijiong 張思炯 (fl. 1765) was appointed magistrate of Ningwu 寧武 County, Shanxi, where he attacked the custom of not burying the dead. He purchased a plot of land to erect a “white bone tower” in which exposed corpses of adults could be stored; he also “purchased land to bury the prematurely dead, which was known locally as ‘the infant cemetery’ (ying’er zhong 嬰兒塚).”[48] Organized efforts to bury infants seem to have become fairly common by the Qianlong period, at least in the northern provinces of Shanxi and Shaanxi, and by the beginning of the nineteenth century, they appear elsewhere, especially in the Lower Yangzi region. They were common enough in the north by the 1820s that Cui Xu 崔旭, who had recently been appointed magistrate of Pu 蒲 County, Shanxi, could write about his own desire to establish a burial ground for children: “I have heard that all other counties have an infant cemetery—one name [for them] is the ‘building for depositing children’ jizilou 寄子樓—to collect and store the corpses of infants, which have been erected through the good work of sincere and benevolent gentlemen. My jurisdiction is the only one without such a building. I have long wanted to construct one, but have not had the ability.”[49] By the early nineteenth century, similar sentiments begin to appear frequently in local histories. Dedicated infant burial spaces later multiplied along with the proliferation of benevolent societies in the nineteenth century.[50]

The origins and evolution of the infant burial movement can be visualized on the accompanying map. By executing targeted searches for terms related to infant burial in large databases such as the Zhongguo fangzhi ku 中國方志庫, we can plot the movement of civic infant burial activities from their beginnings in northern China through their spread into the central and southern parts of the empire.

We can see the movement of different kinds of infant burial activities and infant cemeteries before 1796. It is notable that all of the references prior to 1796 appear in northern China. We can then see how these burial activities shift southward in the post-Qianlong period. Perhaps one of the most interesting discoveries concerns the lack of correspondence between infant burial and philanthropic institutions, at least early on. By overlaying a map of Qing charitable institutions, which was produced by Wang Daxue and his colleagues at Fudan University, we can see that

early infant burial efforts originated in places such as Shanxi, which really had no charitable institutions to speak of. This is somewhat unexpected, since we might assume a close connection between infant burial and elite philanthropy. A

closer correspondence emerges, however, when we overlay a map of “busy counties” (chongxian 沖縣) circa 1820 produced by William Skinner. These are counties that served as the empire’s key administrative and transportation hubs. In this case, the correspondence between infant burial and busy counties in the north is particularly striking. In explaining these trends, my hypothesis is that infant burial efforts were initiated by Qing officials and later picked up by philanthropic elites in other parts of the empire.

Tomb and Tower

The history of baby towers needs to be understood in the context of this broader shift toward infant burial during the Qing, but it also needs to be seen as an extension of the use of “bone towers” (guta 骨塔) as receptacles for the dead. Bone towers have a rich history in China, dating back at least to the arrival of Buddhism during the first centuries of the Common Era. The term “tower,” ta 塔, was an abbreviation of zutapo 卒塔婆, the Chinese transliteration of the word stupa. Over the centuries, in the Chinese context ta has come to denote any kind of raised structure that often, but not always, housed human remains of some kind.[51] In other words, it is a general term that does not necessarily specify what kinds of remains it contains, or whether it contains human remains at all. As a result, prefixes and context are especially important in determining what kind of tower it is. Bone towers typically served a commemorative purpose of some kind, and they could house the remains of either a single person or many people.

The naming practices of bone towers in late imperial China were relatively unsystematic. A perusal of local gazetteers reveals many types of “bone towers” including those for Buddhas, eminent monks, and ordinary people. One of the most important categories was the baiguta 白骨塔—literally “white bone towers”—that were built to house the bleached bones of the abandoned dead. There are hundreds of references to these kinds of towers in local gazetteers from around the empire. Gazetteer entries typically describe when the tower was built and where it was located; they often also include the names of donors who funded the tower. Less common, however, are descriptions of what the towers actually contained. If information is included, it typically says something to the effect that the tower was erected “to collect and store exposed remains” (shoucang puhai 收藏暴骸). Most often this meant the abandoned dead; corpses that accumulated after a war, famine, or epidemic; or “unclaimed” (wuzhu 無主) bodies. What is less clear is whether they included the bodies of children, although one has to assume they did. Another universal name for bone towers was yita 義塔, or “charitable towers.” From what I can tell, most of the structures that were called yita were also used to hold the bones of the abandoned dead, although there were some that were dedicated to children. The description of an yita in the Tongzhi era gazetteer from Badong 巴東 County, Hubei, is typical in this regard: “The yita is in Niukou 牛口, 25 li from the northern boundary of the county. In 1760 (Qianlong 25), local residents Zhang Kaizhe 張楷浙 and Shen Shengzhao 沈聖昭 provided donations to build [the tower] to gather exposed bones (baigu 白骨). They also provided one hillside plot at Zhujiadian 朱家店 and built a stone coffin with 360 apertures to bury corpses found floating in the river after being discarded in the torrent.”[52]

The structures that eventually became known in Western writings as baby towers emerged out of this context. The first observation we can make about “baby towers” is that there really was no such thing, for no other reason than there was little agreement about what to call these structures, and few of them had names that so obviously revealed their contents. Thus, local gazetteers in the Qing include a few instances of yinghaita 嬰骸塔 (“infant skeleton towers”)[53] and ying’er guta 嬰兒骨塔 (“infant bone towers”), which almost certainly were used as receptacles for the infant dead.[54] Cui Xu, who was discussed earlier, uses the term jizilou to describe some kind of building or tower to house infant remains, and De Groot also mentions the term hai’er guisuo 孩兒歸所 (“place of resort for children”) used in this context.[55] We also have a cryptic reference to a guhun youta 孤魂幼塔 (“tower for the orphaned souls of children”), but the gazetteer does not indicate whether the tower actually held human remains or, more likely, whether it was simply a shrine.[56] One of the most common names used for receptacles devoted to housing infant remains was jiguta 積骨塔, or “tower for storing up bones.” In fact, the Shanghai burial towers mentioned in so many writings by Westerners, including those that opened this essay, were referred to in Chinese as the jiguta. In the same way that structures such as baiguta and yita could house remains of all kinds, jiguta also could be used for various purposes. As a result, we cannot assume that when jiguta are mentioned in local gazetteers they were used solely to house infant remains, but there is evidence to suggest that many of them were.

As with the charitable graveyards discussed earlier, infant burial towers were a product of official and elite activism. The Shanghai County gazetteer mentions the creation of jiguta, along with other charitable activities such as building bridges, establishing shrines for the worthy, providing coffins for the poor, donating medicines, and so forth.[57] Similarly, they were built in order to protect corpses from the ravages of animals and the elements. The Jiashan 嘉善 County gazetteer states: “Every time that corpses and coffins were abandoned around the city, they were exposed to the wind and rain, eaten by dogs, and pecked by birds—it was heart-breaking to see. On Grave-Sweeping Day and at the end of the year, local worthies Zhu Juxi 朱菊溪 and Wu Linpu 吳臨浦 paid workers to bury [the bodies] in the grave for abandoned corpses, the jiguta, and the charitable graveyard.”[58] Eager philanthropists not only donated money and land to build these structures, they also contributed funds to provide for their upkeep. In Xinfeng 新豐 Township, Zhejiang, local elites gave land and money to build three jiguta in 1805—one for men, one for women, and one for children. Several local pawnshops provided six thousand yuan each year to manage the towers, and they paid annual operating costs to conduct seasonal charity work on its behalf. Each autumn, they paid to have Buddhist water and land rites performed for the dead; in the winter they paid to have unclaimed and exposed corpses gathered and placed in the towers.[59]

Figure 5. Baby Tower in Zhejiang. China’s Millions (June 1903), 76.

There are several preliminary observations we can make about infant burial towers. First, these structures appear to have been relatively recent, historically speaking. We have two references to jiguta built in the early eighteenth century in Songjiang 松江 Prefecture, but there is no solid evidence that either tower was dedicated to house the corpses of children. We also have one reference to an infant burial tower in Xugou 徐溝 County, Shanxi, that dates from the Qianlong period. All of the other references I have found thus far date from the nineteenth century. This does not mean, of course, that earlier references cannot be found. However, the chronological distribution would seem to suggest that the construction of infant burial towers was a later historical development.

Second, infant burial towers appear to have been rare. After performing an exhaustive search in electronic databases such as the Zhongguo fangzhi ku, which currently includes four thousand pre-1949 local gazetteers, I can find fewer than two dozen references to these structures. So, on the face of it, the infant burial tower does not appear to be a universal fixture of the Chinese deathscape. That said, there are more than six thousand extant gazetteers that are not yet included in this database, which makes it entirely plausible that more references exist. It is also possible that these structures were so common as to not warrant mention in the sources at all. Earlier, we read the comments of Cui Xu, magistrate of Pu County, Shanxi, who remarked, “I have heard that all other counties have an infant cemetery—one name [for them] is the ‘building for depositing children’ jizilou 寄子樓—to collect and store the corpses of infants, which have been erected through the good work of sincere and benevolent gentlemen. My jurisdiction is the only one without such a building.” If reliable, statements such as these would suggest that receptacles of one kind or another (see below) might have been far more widespread than the sources indicate. While Cui might have had reason to exaggerate his infant burial efforts, it is uncertain how he might benefit from confessing that he is a latecomer to the infant burial movement. So, although infant burial towers appear to have been rare, this conclusion should be approached with caution.

Third, the infant burial tower appears much more frequently in sources from the Lower Yangzi region. The overwhelming majority of references we have come from a very small region in and around Shanghai: Songjiang Prefecture in Jiangsu Province (Shanghai County, Qingpu County, Jinshan 金山 County, and Nanhui 南匯 County) and Jiaxing Prefecture in Zhejiang Province (Jiashan County, Pinghu 平湖 County, and Xinfeng Township). It is important to note that some of these communities had multiple jiguta—Pinghu County in Jiaxing had six! Thus, if we were to rely solely on gazetteer data, the evidence would suggest that infant burial towers were predominantly a regional phenomenon. That said, there are several caveats related to geographic distribution that are in order. First, local gazetteers from the Jiangnan region are more plentiful, which could easily skew the data toward that part of the empire, especially when the total number of towers is so low. In other words, there might be more references to infant burial towers from that region, simply because there are more extant gazetteers from that region.

A second issue relates to architectural style. Broadly speaking, infant burial receptacles appear to have built according to at least two different styles during the Qing dynasty. When foreigners commented on baby towers, they usually referred to stand-alone structures of the kind that we see in Figures 5 and 6. In many cases, these buildings were quite elaborate. They were tall buildings with fine stonework and relatively ornate roofs, erected in visible exurban locations. These were the buildings that figured prominently in Jiangnan gazetteers.

Figure 6. Baby Tower 13B-127, Sichuan, ca. 1917. Sydney D. Gamble Photographs, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University. Reused by permission.

However, a second style of building appears to have been more common elsewhere. Some northern sources talk about infant burial receptacles as “pits” or “holes,” and they appear to have been built expressly to blend into the urban environment. As J. J. M. de Groot attested:

In many parts of the Empire we saw filled infant boxes in profusion along city-walls, the lid fixed on by means of frail willow withes or hempen strings. In the chief city of the department of Tsüen-cheu [Junzhou 均州, Hubei?] some large square projectures from the city-walls are generally used by the people as receptacles to throw their dead children into. These curious brick structures, if seen from the outside of the walls, look like salient crenellated bastions, but in reality they are square chambers, quite open at the top, which, having no apertures whatever in the four sides, are only accessible from above by means of ladders.[60]

This sounds remarkably similar to the example we saw earlier with magistrate Wang Chang in Xiaoyi County, Shanxi, who during the Qianlong reign built two receptacles for infants in the city walls. This is not to say that city wall burial sites cannot be found in other locations. In fact, the two styles of tower almost certainly appeared side by side throughout the empire. We have photographic evidence of a “tower” (ta 塔) in Ningbo that was squat and appears to have been built into the city wall, albeit not exactly in the same way as De Groot described.[61]

The point I would like to make here is that the style of tower might have been determined by sources of patronage, which may have had a bearing on how visible they were in local gazetteers. Many of the towers described in northern sources sound as if they were built in a simpler, less conspicuous style, as suggested above. They also appear to have been built primarily by officials as public works projects. Many of the infant burial towers in the south, on the other hand, appear almost monumental by comparison. And, of course, they were monuments—monuments to the generosity of the men who commissioned them. The durability and architectural prominence of more elaborate towers undoubtedly made them a more attractive investment for discriminating donors. It seems reasonable to infer that these towers were more likely to be documented for posterity in local gazetteers. The example of Shanghai is instructive because we know there were multiple infant burial towers in the area—low-lying ones, as well as towers, but the latter attracted far more attention from foreigners. To be sure, there were other reasons towers may have been preferred in the Lower Yangzi region. It might have had something to do with the weather, since finding underground receptacles to contain the dead in the wet southern climate of Jiangnan may have been more difficult than in the north. Indeed, according to Christian Henriot, the infiltration of subsurface water into graves led to a proliferation of unburied coffins in the Shanghai region, and “it was inconceivable to bury one’s dead in such inauspicious conditions.”[62] Nevertheless, in the impassioned charitable economy of nineteenth-century Jiangnan, stand-alone towers may simply have been a more desirable locus for philanthropically minded elites—and thus a more worthy topic of discussion for those same elites—than they were in other parts of the empire.

Toward a History of Infant Burial

The discussion thus far would suggest that there was a dramatic shift in attitude toward the infant corpse in the late imperial period. How do we explain this change? There are a few of explanations I find plausible. The first concerns shifting elite attitudes toward the physical body and anxieties about interment that we see in many of the writings about infant burial. Although common people in the eighteenth century routinely exposed their infant dead expecting they would be consumed by wild animals, the same cannot be said for many officials. In virtually all of these texts, officials express in graphic language their horror that the body parts of children are strewn across the landscape, exposed to the elements, to suffer the munch and crunch of wild animals. In this regard, the prospect that child remains are essentially becoming part of the local food chain suggests heightened anxieties about properly preserving and commemorating human remains. We know from the work of Norman Kutcher that unburied corpses were a growing concern for the Qianlong court. Adult encoffined bodies that were either buried temporarily (fucuo 浮厝) or left for decades exposed to the elements came under fire in the 1740s by officials such as Chen Hongmou 陳弘謀, who considered delayed burial, especially among elite families, to be a serious problem.[63]

These anxieties may have been exacerbated by discussions surrounding cremation during the Qianlong reign. Jurchens and Manchus had traditionally practiced cremation, but this began to change after the Qing dynasty was established and bannermen were encouraged to follow the Chinese practice of interring bodies of the dead. Mark Elliott relates the story of Arigūn, the garrison general at Qingzhou, who advocated cremating the bodies of bannermen who died at their postings, in order to facilitate the delivery of their remains back to the capital. The general reasoned that cremated remains were more economical to store and transport than entire corpses, so cremating the bodies of dead bannermen would free up valuable garrison resources. Qianlong rejected this argument, stating that bodies should be buried according to “ancient” (i.e., Chinese) custom. Yet Elliott marshals evidence to suggest that cremation may have persisted well into the nineteenth century.[64] It is possible that the positive reception of infant burial efforts promoted by Fan Guangxi in Shaanxi in 1706 was somehow tied to similar concerns with the banners, since all three of the highest-ranking officials who issued their own orders to prohibit infant exposure and promote burial—Governor-General Boji, Shaanxi Governor Ehai, and Lieutenant Governor Eluo—were conspicuously Manchus.

In other words, by the beginning of the eighteenth century, the state was reiterating on several fronts its commitment to burial as the only orthodox means of disposing of the dead, and it would make sense that infant burial would eventually become implicated in this discussion. No doubt, anxieties about the exposed body were exacerbated by the proliferation of corpses during the Qing, as population growth, urbanization, and rebellions increasingly led to a surplus of unruly bodies.[65] It is plausible that these fears contributed to a growing feeling that corpses—adults or infants—were symptoms of increasing social disorder that needed to be remedied.

In light of this movement toward orthodoxy, efforts to reform infant burial, particularly official campaigns against exposing infant corpses, should also be understood as part of a long-standing Confucian polemic against Buddhism. As the discussion earlier indicated, parents very often justified exposing their infant dead by appealing to folk understandings of fertility and transmigration. As a result, it is plausible that the concern with reincarnation and much of the terminology surrounding the consumption of corpses by wild animals was inspired by folk Buddhist understandings of infant burial. As Liu Shufen has demonstrated, corpse exposure (lushizang 露屍葬) became a popular method of burial in northern China during the medieval period. Liu explains, “Many Buddhists appear to have been inspired by the example of the Śākyamuni Buddha, who in one of his previous incarnations offered his body to wild animals. Dāna of the dead was to be accomplished by offering one’s body to living creatures through exposure in rivers or forests.”[66] Indeed, much of the imagery that Liu says was employed by Buddhist monastics and lay people to extol the feeding of corpses to animals—replete with the evocative depictions of pecking, sucking, and gnawing—sounds strikingly similar to the descriptions of this practice by Qing officials. That officials also relied heavily on canonical Confucian texts in their campaigns to eliminate the practice suggests that infant burial had become a site in the larger ideological battle between Buddhists and Confucians. Although it is beyond the scope of this essay, there is a distinct possibility that the medieval practice of corpse exposure had become so deeply entrenched in northern China that it persisted well into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The movement toward infant burial also suggests a rise in sentimentality toward children as a whole and a corresponding sensitivity toward infant corpses in particular. Again, virtually all the lengthy discussions we have about why infants deserved to be buried speak extensively about the natural love or care that parents feel for their children. It was precisely the peculiar character of the parent-child attachment—a cosmic bond reflected in the principles of Heaven that were expressed in human relationships, as well as in the natural world more broadly—that militated against anonymous or indecorous burial. One of the more interesting prospects in thinking about this shift is the possibility that it may have arisen out of a growing concern for young girls in late imperial China. Hsiung Ping-chen talks in her work about the emergence of a “daughter-loving culture” in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties through which elite men increasingly expressed their affection for their living daughters, as well as their acute sorrow when their daughters died young.[67] Considering that the number of exposed infant remains would almost certainly have been disproportionately female, it would make sense that a growing concern for living girls would translate into concern for dead ones. The gazetteer from Yongping Prefecture, Zhili, records the efforts of Wang Ruizheng 王瑞徵 (fl. 1828), who in the early nineteenth century built a “charitable cemetery for burying infants.” Wang wrote about the customs in his hometown, saying that “it is common to see dead girls (nüyou 女幼) abandoned in the suburban wilds, where their corpses are exposed and cruelly consumed by wolves and dogs. People walking on the road cannot help but weep at this state of affairs and ask how parents could in the end could be so malicious.”[68] Wang later talks about why proper burial for both “sons and daughters” is so important, but it was clearly the plight of girls that made the deepest impression on him. Of course, burial was not the only field within which the social value of girls was changing. During the Qing, we see a range of elite philanthropic activities—a movement I would call “girlanthropy”—in which the young female body was singled out for reform: campaigns against infanticide, the establishment of foundling homes, campaigns against footbinding, and so forth.

Clash of Civilizing Missions

To bring this discussion full circle, it is worth noting that many of the same fears Chinese elites had about infant corpses map onto the concerns of Western visitors to China, albeit for different reasons. Much has been written about the profound shift in mourning and burial practices that took place in both Britain and the United States during the nineteenth century. Elites in both these countries were distressed by what they interpreted as a spate of infanticide and child abandonment at home. In Britain, the poor had difficulty burying stillborn infants after the passage of legislation that meant to ease crowding in urban cemeteries. As a result, a London coroner in 1855 remarked that he was finding an increasing number of dead babies in the streets.[69] The same thing was true in the United States, where “the status of foundlings reached crisis proportions. Baby desertion threatened to become an epidemic, particularly in cities, where despairing mothers could abandon their newborn more easily than in small towns. In New York City alone, for example, infanticide resulted each month in the discovery of 100 to 150 bodies in places such as empty barrels or the rivers.”[70] Both countries also witnessed rising concerns about “baby-farming,” a practice whereby women allegedly entrusted their newborns to paid “foster” care, which usually resulted in the mistreatment or death of the babies.[71] Thus, when foreign visitors commented on the association between so-called baby towers and infanticide during the mid-nineteenth century, they were in many ways participating in a discourse that began long before they even set foot in China.

Apprehensions about traditional burial practices were a shared Anglo-American phenomenon, as well. In the early nineteenth century, British burial grounds were becoming extremely overcrowded. In the words of Lee Jackson, “The consequences, wherever demand exceeded supply, were decidedly unpleasant. Coffins were stacked one atop the other in 20-foot-deep shafts, the topmost mere inches from the surface. Putrefying bodies were frequently disturbed dismembered or destroyed to make room for newcomers. Disinterred bones, dropped by neglectful gravediggers, lay scattered amidst the tombstones; smashed coffins were sold to the poor for firewood.”[72] Observers also complained about the stench of the dead, which was increasingly implicated in public health concerns. Many Londoners were concerned that “miasma” produced by decomposing bodies was a medium for the spread of diseases such as cholera. Reputedly “unsanitary” traditional graveyards were eventually eclipsed by spacious new “garden cemeteries” that promised to be more soothing and salubrious than their predecessors.[73] Thus, this nineteenth-century desire for a burial solution that was both olfactorily and horticulturally pleasing set certain expectations for what a proper burial ground should be. And it was precisely these expectations that the infant burial towers of China did not fulfill.

I hope it is now relatively clear what a more complete history of the baby tower might look like. What were called “baby towers” were actually a historically recent addition to the late imperial deathscape that could be found primarily in the area immediately surrounding Shanghai, the place in China where the foreign presence was arguably most pronounced. In many respects, they were a peculiar product of two overlapping concerns that had roots in different regions of the empire: campaigns to encourage infant burial that emerged in northern China in the early eighteenth century, combined with a preference for burial towers that were built by philanthropists in the Lower Yangzi region. In a pattern that followed colonial encounters elsewhere, such as debates over sati in India, many foreign visitors to China (mis)took what was a geographically circumscribed burial practice and applied it to the empire as a whole. In the process, baby towers became a touchstone for concerns about infanticide, childhood, gender, class, and death that connected audiences both in China and at home. Their existence, of course, could also be used to justify the continued presence of “benevolent” foreign agents who advanced their own “enlightened” social and political programs.

One of the most delicious ironies of the baby tower phenomenon relates to what we might call the “clash of civilizing missions” these structures embodied. On the one hand, we had activist Chinese officials and elites who sought to reform what they considered to be the barbaric burial practices of the benighted masses. On the other hand, we had Western visitors who sought to reform what they considered to be the barbaric burial practices of the benighted Chinese elites. In both of these cases, the so-called “baby tower” shifted the ontological horizon of each, creating new possibilities for action and suggesting new programs to be pursued. Perhaps it is only fitting that in the Qingpu County gazetteer from 1934, a Chinese author—no doubt one of Shanghai’s emerging “modern” elites—would contemptuously describe the jiguta that still stood outside that city in a way that would have resonated with many of his Western predecessors: as a fetid, archaic testament to a past generation of misguided do-gooders.[74]

Notes

Source of image at the top of this essay: “A Baby Tomb in China.” Ballou’s Monthly Magazine (January-June 1870), 109.

I would like to thank the scholars who so graciously provided feedback on this project at various stages, including Joanna Handlin-Smith, Ernest P. Young, Peter Carroll, Lee Haiyan, Marc Moskowitz, Fabian Drixler, Michael Chiang, and all of the participants at the “Digging Up the Chinese Dead” workshop at Harvard University in December 2015. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Dagmar Schäfer and the Chinese Local Gazetteers Project group at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin for all of their help. Without the use of MPI’s facilities and databases, as well as the generous technical assistance of Chen Shih-Pei and Che Qun, this project would not have been possible. Research funding for this project was provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Faculty Growth and Development Committee at the College of Idaho.

[1] According to Chinese rendering, a child is one sui old at birth and adds an additional sui at each lunar New Year. Consequently, a child who is born in the eleventh month of the lunar calendar would be two sui old, despite being only two months old by Western calculations. As a rule of thumb, a child of eight sui is approximately seven years old, or slightly younger.

[2] Bayard Taylor, A Visit to India, China, and Japan in the Year 1853 (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1855), 323–324.

[3] George Wingrove Cooke, China: Being ‘The Times’ Special Correspondent from China in the Years 1857–58 (London: G. Routledge, 1858), 99.

[4] Mary Isabella Bryson, Child Life in Chinese Homes (London: Religious Tract Society, 1885), 17.

[5] London and China Telegraph, January 11, 1869, 25.

[6] Lynn Morgan, “Getting at Anthropology through Medical History: Notes on the Consumption of Chinese Embryos and Fetuses in the Western Imagination,” in Marcia C. Inhorn and Emily Wentzell, eds., Medical Anthropology at the Intersections: Histories, Activisms, and Futures (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 41–64.

[7] One of the few sustained analyses of baby towers in the secondary literature—Michelle King’s Between Life and Death—is found in a monograph about infanticide, not burial practices. See Michelle King, Between Life and Death: Female Infanticide in Nineteenth-Century China (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), especially chap. 3.

[8] The concept of infancy in later imperial China was vague. Although some medical texts referred to infancy as the period of childhood from birth to around nineteen months, the term “infant” (ying’er) could refer to any child younger than seven sui for girls and eight sui for boys. I employ it in this more expansive sense, although I also use terms such as “child” or “young child” as necessary. See Charlotte Furth, “From Birth to Birth: The Growing Body in Chinese Medicine,” in Anne Behnke Kinney, ed., Chinese Views of Childhood (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1995), 180–181.

[9] Tina Philips Johnson and Yi-Li Wu give an infant mortality figure in the early Republican period of 250–300 deaths per one thousand births. Mary Brown Bullock and Bridie Andrews, Medical Transitions in Twentieth-Century China (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014), 56.

[10] Mark Elliott, Emperor Qianlong: Son of Heaven, Man of the World (New York: Longman, 2009), 47.

[11] Yili zhengzhu 儀禮鄭注, Sibu beiyao ed., (Taipei: Chung Hwa Book Company, 1984), vol. 2, 11:14a.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Patricia Ebrey, Chu Hsi’s Family Rituals: A Twelfth-Century Manual for the Performance of Cappings, Weddings, Funerals, and Ancestral Rites (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), 95–96.

[14] Susan Naquin, “Funerals in North China: Uniformity and Variation,” in James L. Watson and Evelyn S. Rawski, ed., Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 46.

[15] J. J. M. de Groot, Religious System of China, Book 1 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1894), 1075.

[16] Ibid., 1387.

[17] David F. Lancy, “Babies Aren’t Persons: A Survey of Delayed Personhood,” in Hiltrud Otto and Heidi Keller, ed., Different Faces of Attachment: Cultural Variations on a Universal Human Need (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 87.

[18] Chinese Text Project, “Tan Gong I 檀弓上”, verse 12, trans. James Legge.

[19] Wang Sisheng, “Proclamation Prohibiting the Discarding of Infant Remains” 禁止拋棄嬰骸示, Shuozhou zhi 朔州志, (1735 ed.), j.12, 22b (ZFZK, 723). In this essay, I have referenced page numbers according to the pagination found in the Zhongguo fangzhi ku 中國方志庫 (hereafter ZFZK).

[20] Ibid., j.12, 23a (ZFZK, 724), trans. James Legge, “Tan Gong II 檀弓下”, verse 203.

[21] Liu Shiming, “Proclamation to Collect and Bury the Remains of Infants” 收埋嬰兒骸骨示, Shuozhou zhi 朔州志, (1735 ed.), j.12, 21b (ZFZK, 721).

[22] Ji Shilin, “An Exhortation to Bury Infants 勸埋嬰兒說,” Xu Gaoping xianzhi (1880 ed.), j.15, 30b (ZFZK, 532).

[23] Fabian Drixler, Mabiki: Infanticide and Population Growth in Eastern Japan, 1660–1950 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 139.

[24] Zhaocheng xianzhi 趙城縣志 (1760 ed.), j.22, n.p. (ZKFK, 126).

[25] Fenyang xianzhi 汾陽縣志 (1851 ed.), j.13, 48a (ZFZK, 1175).

[26] Ji, “An Exhortation to Bury Infants,” j.15, 31a (ZFZK, 534).

[27] Wang, “Proclamation Prohibiting the Discarding of Infant Remains,” j.12, 23a (ZFZK, 724).

[28] Yongping fuzhi 永平府志 (1711 ed.), j.5, n.p. (ZFZK, 352).

[29] Zhaocheng xianzhi 趙城縣志 (QL25 ed.), j.22, n.p. (ZKFK, 1266).

[30] Wuyang xianzhi 舞陽縣志 (1835 ed.), j.6, 6b (ZFZK, 261).

[31] Yiyang xianzhi 伊陽縣志 (1838 ed.), j.1, n.p. (ZFZK, 115).

[32] Yanchang xianzhi 延長縣志 (undated Qianlong manuscript), n.p. (ZFZK, 303).

[33] Michael Simpson Culbertson, Darkness in the Flowery Land (New York: Scribner, 1857), 167. See also the discussion of “resentful fetal souls” in Marjorie Topley, “Cosmic Antagonisms: A Mother-Child Syndrome,” in Arthur P. Wolf, ed., Religion and Ritual in Chinese Society (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1974), 246. See David E. Pollard, Real Life in China at the Height of Empire (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2014), 101.

[34] Adapted from Wang Qingren, trans. by Yuhsin Chung, Herman Oving, and Simon Becker, Yi Lin Gai Cuo: Correcting the Errors in the Forest of Medicine (Boulder, CO: Blue Poppy Press, 2007), 7. I would like to thank Yi-Li Wu for bringing this source to my attention.

[35] Timothy Brook, Jerome Bourgon, and Gregory Blue, Death by a Thousand Cuts (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 14–15.

[36] Qingpu xianzhi 青浦縣志 (1878 ed.), j.20, 24b (ZFZK, 1323).

[37] Ji, “An Exhortation to Bury Infants,” j.15, 31a (ZFZK, 534).

[38] Henrietta Harrison shows that in addition to the mutilation of bodies, babies were also beaten in order to dissuade their spirits from returning. See Henrietta Harrison, “Penny for the Little Chinese: The French Holy Childhood Association in China, 1843–1951,” American Historical Review 13.1 (2008), 82.

[39] Donald Harper, “Spellbinding,” in Donald Lopez Jr., ed., Chinese Religions in Practice (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 248–249. See also the discussion by Marc Moskowitz, The Haunting Fetus: Abortion, Sexuality, and the Spirit World in Taiwan (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2001), 164.

[40] Liu, “Proclamation to Collect and Bury the Remains of Infants,” j.12, 22a (ZFZK, 722).

[41] Ji, “An Exhortation to Bury Infants,” j.15, 32a (ZFZK, 536).

[42] Chinese Text Project, “Yue Ling 月令,” verse 7, trans. James Legge.

[43] Jeff Snyder-Reinke, Dry Spells: State Rainmaking and Local Governance in Late Imperial China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center), chap. 2.

[44] Joanna Handlin Smith, The Art of Doing Good: Charity in Late Ming China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 221–222.

[45] Liang Qizi, Shishan yu jiaohua: Ming Qing de cishan zhuzhi 施善与教化: 明清的慈善组织 (Shijiazhuang, Hebei: Hebei jiaoyu chubanshe), 278-306.

[46] Linyou xianzhi 麟遊縣志 (1708 ed.), j.3:33, 3a–5a (ZFZK, 124-128).

[47] The gazetteer also states, “Although many people now know they should bury, they [still] do not deposit [children] in the cavities.” Xiaoyi xianzhi 孝義縣志 (1770 ed.), j.1, 14a (ZFZK, 316).

[48] Ningxiang xianzhi 寧鄉縣志 (1941 ed.), 先民傳二十四, 清, 5b (ZFZK, 2574).

[49] Cui Xu, “Draft for Establishing Infant Cemeteries 擬立嬰兒冢文” Yongji xianzhi 永濟縣志 (1886 ed.), j.24, 42b-43a (ZFZK, 2105-2106).

[50] The gazetteer from Jiangning 江寧 Prefecture in Nanjing, for example, records that the work of the Fellowship of Goodness Hall (Tongshantang 同善堂) “established a charitable cemetery for the burial of infants” and the Community Goodness Hall (Gongshantang 公善堂), which “buried infants in the drum tower.” Often these graveyards were attached to foundling homes, as well. See Xuzuan Jiangning fuzhi 續纂江寧府志 (1880 ed.), j.9.1, 26a (ZFZK, 1152).

[51] See Charles Muller’s Digital Dictionary of Buddhism, “塔.”

[52] Badong xianzhi (Guangxu ed.), j.16, n.p. (ZFZK, 216).

[53] See, for example, Xugou xianzhi 徐溝縣志, j.4, 16a (ZFZK, 106), and the two towers in Hequ xianzhi 河曲縣志 (1872 ed.), j.6, 62b (ZFZK, 747).

[54] Haining zhouzhi 海寧州志 (1922 ed.), j.6, n.p. (ZFZK, 738).

[55] De Groot, Religious System of China, Book 1, 1388.

[56] Fenghua xianzhi 奉化縣志 (1877 ed.), j.3, 26a (ZFZK, 205)

[57] Shanghai xianzhi 上海縣志 (1918 ed.), j.2, n.p. (ZFZK, 199).

[58] Chongxiu Jiashan xianzhi 重修嘉善縣志 (1892 ed.), j.5, n.p. (ZFZK, 406).

[59] Fan Hongxiang 范洪祥, “Xinfeng’s Bone Burial Tower” 新豐瘞骨塔, Jiaxing gushi 嘉興故事.

[60] De Groot, Religious System of China, Book 1, 1387.

[61]See A "Baby Tower," Ningpo, c.1870.

[62] Christian Henriot, Scythe and the City: A Social History of Death in Shanghai (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016), 146.

[63] Norman Kutcher, Mourning in Late Imperial China: Filial Piety and the State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 144-148.

[64] Mark Elliott, The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001), 264.

[65] Jeff Snyder-Reinke, “Afterlives of the Dead: Uncovering Graves and Mishandling Corpses in Nineteenth-Century China,” Frontiers of History in China 11.1 (2016): 1-20.

[66] Liu Shufen, “Death and the Degeneration of Life: Exposure of the Corpse in Medieval Chinese Buddhism,” Journal of Chinese Religions 28.1 (2000): 6.

[67] Hsiung Ping-chen, A Tender Voyage: Children and Childhood in Late Imperial China (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005), 195-204.

[68] Yongping fuzhi 永平府志 (1879 ed.), j.43, n.p. (ZFZK, 3134).

[69] Lee Jackson, Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight against Filth (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014), 132.

[70] LeRoy Ashby, Endangered Children: Dependency, Neglect, and Abuse in American History (New York: Twayne, 1997), 34. See also Julie Miller, Abandoned: Foundlings in Nineteenth-Century New York City (New York: New York University Press, 2008).

[71] See Ginger Frost, Victorian Childhoods (New York: Praeger, 2009), 157-158.

[72] Jackson, Dirty Old London, 105.

[73] For a useful overview of the emergence of garden cemeteries, see Sarah Tarlow, “Landscapes of Memory: The Nineteenth Century Garden Cemetery,” European Journal of Archaeology 3.2 (2000): 217-239.

[74] Qingpu xian xuzhi 青浦縣續志 (1934 ed.), j.24, 6a (ZFZK, 849).