This essay, however, is not about remembrance. It is about reimagining and reconstructing the imprint that death left behind in various ways and at different scales in the city. Nowadays, very few people in Shanghai can imagine what the city looked like in the mid-nineteenth century, a walled compound surrounded by graves and burial grounds. Even the institutions and the infrastructure of the Republican era up to 1949 are little known to historians. All the urban markers from that period, especially those that embodied funeral and burial practices, have disappeared.

The establishment of foreign settlements in the city in the mid-nineteenth century set in motion a process that challenged the presence of the graves and burial grounds that surrounded Shanghai and redrew the landscape of death outside its walls. It was not so much the foreign settlements per se that created a problem for the preservation of graves and burial grounds as the process of rapid urbanization that accompanied the development of the settlements. With or without the foreign settlements, urbanization would have caused many, if not most burial grounds to be relocated, as most of them were low-status charity graveyards that could hardly defend themselves against urban encroachment. Urbanization continued to squeeze cemeteries out of the city, except for the more resilient and better protected foreign or guild cemeteries. In the 1950s, however, the People’s Government launched a drastic policy to eliminate all funeral activities from urban areas and started to relocate all the cemeteries that had been established intra muros. Thereafter, the political frenzy of the Great Leap Forward, followed by the political turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, led to the destruction of many, if not most, cemeteries. There was no relocation of the graves. The places were simply ransacked and flattened.

This essay provides a spatial analysis and reading of the fate of burial grounds and cemeteries in modern Shanghai. It contends that the combination of urban development (before 1949) and political decisions and movements led to the complete erasure of cemeteries in the city. While a few places were restored in the late 1980s–early 1990s, the handful of new cemeteries the Shanghai government authorized were in remote locations far from the city center and faced little risk of being caught up in Shanghai's urban sprawl. The experience of Shanghai both before and after 1949 clearly presages the process now at work in Chinese cities since the beginning of the reform era.

A Diverse and Changing Landscape: From Burial Grounds to Cemeteries

For centuries, the inhabitants of Shanghai buried their dead in the countryside, just outside the city walls. There was nothing akin to the church graveyards of European cities where people were buried, either under the church itself (in catacombs) or in the plot of land around it. Although sources occasionally mention family tombs within the city’s walls, this was exceptional. The norm was definitely to remove the dead from the space of the living. As discussed below, there were two main types of burial grounds: individual tombs, placed anywhere in the fields, and charity graveyards. The main burial grounds were owned by benevolent associations and guilds. Yet the land in the countryside was also densely populated, with numerous villages dotting the landscape. Villagers usually had a small burial ground, often related to a lineage, but many chose to bury their dead in individual graves in the middle of open fields, a location defined by a Taoist priest or a geomancer. The landscape of death, however, was much more complex due to the presence of tens of thousands of unburied coffins (ting guan bu zang 停棺不髒) all around the city.

These two factors—the practice of burial extra muros for the urban population and the dense network of villages around Shanghai—produced a very particular geography, almost a topography, of death around the city. The first Western visitors were struck by the multitude of tombs that dotted the rural landscape. A column of soldiers that marched from Wusong, fourteen miles north of Shanghai, to the city in 1842 reported that "graves were in every field—mounds of earth, some hollowed into vaults, others with the coffin resting on the top, and covered with matting."[2] One century later, the Japanese and Chinese armies often made use of the tumuli formed by these rural tombs as defense works.[3] Of course, there is no way to know now how many and where these tombs were located. They are precisely the least documented form of burial as no authority formally regulated them until the 1930s, in a vain and failed attempt to induce peasants to bury their dead in cemeteries.[4] These tombs emerged from anonymity only when a decision was made to remove them by force, usually for the sake of military installations such as airfields.

Thus, when the British, then the French and the Americans, were allotted a piece of land to establish their respective settlements, they did not find an empty land, a landscape of mud and marshes as the colonial story goes, but a land peppered with village communities and their tombs and graveyards. The British were a bit less concerned about the issue of graves on their territory. Their land was far north of the city wall, with a small river running along its southern border. The eastern section ran along the Huangpu River, a muddy and inauspicious land for burials. More importantly, there was no major graveyard, at least before the settlement was extended in 1899. While the Americans were in a very similar position, the French inherited the worst possible location, a narrow stretch of land between the city walls and the southern border of the British Settlement. This was an area filled with tombs, charity graveyards, and guild graveyards. From the beginning, the French officials made it their policy to systematically remove all the individual tombs and graveyards from their territory.[5] It is not an exaggeration to say that this bordered on an obsession which, in one case, led to violent confrontations with a major Chinese guild.[6]

The treaties gave Westerners the right to have reserved territories for the sake of trade, first in five ports, then in a long string of port and inland cities. The peasants who owned land in the territories earmarked for a foreign settlement could not refuse to sell their land to whoever wanted to acquire it. Yet, careful consideration was given to the issue of tombs and graveyards. The Land Regulations that defined the rights and obligations of foreigners in each settlement, especially the conditions under which they could acquire land, placed restrictions for the protection of tombs and graveyards: “If there are graves or coffins on the land rented, their removal must be a matter of separate agreement, it being contrary to the custom of the Chinese to include them in the agreement or deed of sale.” Another article (XI) actually forbade unilateral action: “In no case shall the graves of Chinese on land rented by foreigners be removed, without the express sanction of the families to whom they belong, who also, so long as they remain unmoved, must be allowed every facility to visit and sweep them at the established period, but no coffins of Chinese must hereafter be placed within the said limits, or be left above ground.”[7] Of course, the same rule applied to the graveyards owned by charities and guilds.

In the early history of the British Settlement, the issue of individual tombs did not lead to much trouble. The Chinese owners and foreign renters usually came to an agreement, either by paying a sum of money to have tombs removed or, more rarely, by excluding tombs and the small plot of land that surrounded them from the sale.[8] Over time, however, this practice tended to disappear. In the French Concession, the consul general and the municipal committee sought to systematically eliminate all the tombs and graveyards. It took about two decades to remove them all, except for one (belonging to the Siming Guild). Aside from dealing with individual tombs, the French also had to deal with many charity graveyards and three guild graveyards. These charities yielded without much resistance to the requests to relocate their graveyards beyond the borders of the French Concession (to be caught up again when the concession was extended in 1900 and again in 1914).

One of the Fujian Guilds (we believe it was the Quanzhang Guild) and the Chaozhou Guild both owned premises, namely a guild hall, a coffin repository, and, for the Fujian Guild, a small cemetery. The Chaozhou Guild ceded its premises to the French army, while the Fujian Guild eventually agreed to sell its land and premises to the French municipality in 1861. The French took advantage of the destruction of the Small Sword Society in an uprising in 1853–1855 and the subsequent weakening of the Fujianese and Cantonese after their involvement in the rebellion.[9] The French consul wrote almost ecstatically that “the expropriation of the Fujianese and Cantonese cemeteries, so often urged and always refused, has finally been accomplished. There is no longer any trace of the famous baby tower, nor of its pestilent surroundings.”[10] Yet the French encountered their own island of resistance to their pressure to rid the settlement of all graveyards and coffin repositories. The influential Siming Guild persistently demurred and refused to touch the remains of its members. It took two confrontations, in 1874 and in 1898, to convince the leaders of the guild that the time had come to relocate its graveyard and coffin repository.[11]

There is no direct record of the tombs and graveyards that were removed from the foreign settlements in the early phase of their history. Nonetheless, it is possible to make a partial reconstruction of the existing tombs and graveyards thanks to the title deeds, the documents that sealed a sale between a Chinese landowner and a foreign settler. A systematic analysis of the earliest title deeds—those of the first two decades of the settlements—has generated a substantial list of land plots (140) on which a tomb or a graveyard was located.[12] The map produced on the basis of this list—again it is only a partial view of reality—confirms that the northern and western periphery beyond the city wall was used as a burial ground. We also know that there were charity and guild graveyards in the southern outskirts, but they were not documented at the time. The distribution of the tombs shows that as the foreign settlements expanded, their territory was bound to include land with village communities, tombs, and graveyards, as well as burial grounds owned by the guilds that had sought to relocate their graves away from the city walls or land ceded to foreigners. In fact, the guilds and benevolent associations bought land further west and south to establish graveyards, only to later face unrelenting urban sprawl.

If we overlay this geography of death with the successive territorial extensions of the International Settlement and of the French Concession, it becomes clear that these tombs and cemeteries stood in the way of land development and the construction of roads and eventually housing. The predominant mode of construction in Shanghai from the 1850s onward was the so-called lilong 裡弄. Interestingly, the authorities in the two settlements differed in their rendering of the term. The foreign-run Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC) named them after their function as passageways, namely “lanes,” whereas the French Municipal Council placed the emphasis on their role as housing, namely cités. What it comes down to, however, was that lilong were densely built up housing units erected on individual plots of land with no space in-between, except for the main roads on all four sides. There was no room left for tombs. While tombs may have been protected in the initial title deed, they could not survive the onslaught of urban development.

While tombs and cemeteries were the most obvious forms of burials that stood in the way of urban development, they were not the only markers of death in the landscape in and around the city. There was both an inconspicuous and a very conspicuous physical presence of death. The coffin repositories of the guilds represented the former in the form of closed compounds devoted to storing the coffins of their members, pending their return to their native place for burial. Except for a few rare cases, these repositories were located outside the city walls. After the establishment of the foreign settlements, guilds usually chose land to the west and south of the city walls or, much later on, in Zhabei, on the far side of Soochow Creek. The spatial distribution of coffin repositories did not change much over time, except for the opening of new ones as new guilds emerged in Shanghai.

A major change occurred with the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 when the near complete stoppage of river traffic, then the fear of losing coffins on the way, led most Shanghai residents to keep their coffins in the city. This gave birth to commercial coffin repositories that supplemented, then supplanted, the overcrowded guild repositories. The commercial repositories colonized the Western District of the International Settlement and beyond, in the space delimited by the railway line. After 1945, the municipal government forced them to evacuate the stored coffins—about a hundred and fifty thousand—but civil war again slowed down the process which only the Communist government eventually completed within two years after it took over the city.[13] The coffin repositories represented a crucial element of the social infrastructure that supported the management of death in the city. They offered a temporary station in the movement of coffins from home to native place.

Finally, the issue of grave relocation involved another facet of death in and around the city: the widespread practice of “quasi burial.” This took the form of above-ground coffins (ting guan bu zang). Although most such burials were in the countryside around Shanghai, it was quite frequent to find coffins left unburied on vacant land in the city, mostly in the foreign settlements. The municipal archives abound in reports of abandoned coffins in the less frequented part of the city. This practice was not limited to Shanghai—it was true in the whole Jiangnan region—but due to the size of its population, including its hinterland, the figure for unburied coffins was staggering. Under the Qing, the local magistrates repeatedly banned the practice and organized sweeps by the benevolent associations to have the coffins buried. Yet the threat of fines failed to deter people from persisting in this practice. In the late 1940s, the municipal government still had to organize campaigns to collect these coffins and have them cremated. The Bureau of Public Health surveyed the municipal districts in 1929 and came up with a total of a hundred thousand unburied coffins. In 1936, the Shanghai Public Benevolent Cemetery (SPBC) carried out a new survey that placed the number of unburied coffins in a large area around Shanghai at approximately a hundred and fifty thousand.[14]

In thinking about the presence and movement of dead bodies in the city, therefore, one needs to keep in mind this particular topography made up of both permanent features (individual tombs, burial grounds, and cemeteries) and temporary places of rest (coffin repositories, above-ground coffins). While this essay focuses on the permanent locations—at least those intended to be permanent, but in fact exposed to removal and relocation—the movement and displacement of dead bodies in and around the city from the mid-nineteenth century to the early 1950s represented a wider range of circulations within the urban space and its periphery.

Grave Relocation in Modern Shanghai

In late imperial and republican Shanghai, grave relocation resulted from three main factors. The first two—administrative fiat and urbanization—were clearly related. The third factor—war—was limited to the Sino-Japanese War period. Administrative intervention involved mostly two issues: the construction of new roads or the widening of thoroughfares or the construction of buildings, usually large and public facilities (courts, schools, etc.). Urbanization was a silent process that repeatedly led the owners of cemeteries—guilds and benevolent associations—to consider it in their best interests to close the cemetery, to relocate the graves to a new place in the countryside, and to turn the freed land into rental housing. The main reason was, on the one hand, the difficulties that the densification of construction and flow of people created in accessing the property and organizing burials. On the other hand, the guilds and benevolent associations could derive a substantial income from the sale of land or rental housing to fund their operations. Although a decision to vacate a cemetery was rarely made spontaneously, a small nudge by the authorities was often all that was needed.

The main issue the historian faces in documenting the process of grave relocation is the silence of the archives or even just silence. Nevertheless, I have been able to identify and locate 128 burial grounds around Shanghai. This falls short of the actual number, which probably ran into the 150 to 160 range. In most instances, burial grounds just faded away from the urban scene. The cases that we know of are those that created a confrontation and a debate that spilled into the press. In addition, the owners of burial grounds sometimes published press announcements to inform the families that they were planning to dig up the graves and remove the mortal remains to another location. The families were given an opportunity to come forward and themselves take care of the removal and to choose an alternate location for reburial. Yet, it is obvious that a documentary silence shrouded the displacement of the vast majority of burial grounds. The examples I examine below represent exceptional cases and are a small sample of the continuous and sub-rosa process that pushed burial grounds further away from the urban area or simply erased them.

Administrative Fiat

The encounter between charity graveyards and urbanization caused friction but rarely serious tension. In the foreign settlements, the issue was more sensitive in the French Concession, although it became an issue only after the last extension in 1900. In general, the benevolent associations took action when they realized that urban development made it difficult to maintain a charity graveyard in the middle of houses and factories. In the International Settlement, the Shanghai Municipal Council generally accommodated existing graveyards as long as they did not threaten public health. In 1926, however, the council prohibited the further use of a graveyard owned by the Tongren Fuyuantang benevolent association along Sinza Road, especially because the coffins there were barely buried. The initial complaint had come from local residents, who suffered the stench emanating from the graveyard during the summer.[15] In the French Concession, serious conflicts had erupted in handling the issue of the Siming Guild graveyard. Eventually, the guild removed all the remains to a new location, though not without a fight.[16] In most cases, when graveyards got in the way of roadwork or construction or simply were the subject of private transactions, negotiations prevailed. Yet the process was not always free of tension.

In March 1873, the Tongrentang benevolent association decided to rent out the land of a graveyard located along the Rue du Consulat, near the police station. It entrusted the Tongren Fuyuantang with the removal of the remains to its graveyard in Luojiawan. The affair appeared in a paper that criticized the association for renting out the land for money it did not need.[17] In 1922, the French Municipal Council required the Tongrentang to vacate another 6.6-acre (40-mu) graveyard and to relinquish the land for the construction of the Franco-Chinese Municipal School. The opposition to the removal of the graves did not come from the benevolent association itself, but from community leaders who believed the Tongrentang did not have the right to dispose of the land. The polemical debate that erupted in the meetings spilled over into the press, which reported on the issue for more than two months. The graveyard had been established in 1797 in a rural area, but a hundred and thirty years later even the Chinese authorities admitted it was out of place in what had become an urban environment. This dispute underscores how sensitive the issue of displacing mortal remains was for some Chinese who contended that economic reasons did not justify disturbing buried bodies. With great care, the remains—even down to the hair—of the 328 buried bodies, mostly men, were eventually removed.[18]

The issue of removing graves was not limited to the foreign concessions. In September 1907, merchants and literati wrote jointly to the Shanghai City Council calling for a new road to connect West Gate Road and Xujiahui Road. The area had become very congested and the existing road was crowded with carts and people, while a proposed French-built tramway was bound to create even more traffic. The road would cross a 5-acre (30-mu) graveyard the Tongren Fuyuantang owned. The association had exposed itself to criticism for haphazardly placing coffins—some hardly buried—in the graveyard, which threatened public health in the view of the city council. The charity approved the removal, but its chairman reminded the council of three earlier conflicts over graveyards and questioned why Chinese graveyards were displaced from residential areas while the French cemetery (Baxianqiao) was never challenged.[19] In November 1914, the Shanghai City Council again planned to condemn a charity graveyard for children in order to build a new road, but it failed to obtain the transfer of the land. In 1920, the issue was still under discussion.[20] The magistrate of Shanghai County was more successful in obtaining the removal of another Tongrentang cemetery to make way for the new local court of justice.[21]

After World War II, the municipal government attempted to reduce the presence of burial grounds within the urban districts. In 1947, it ordered the removal of all the graves from the Lingnan Cemetery.[22] The Cantonese Native-Place Association in charge of the cemetery published announcements in the press, leading many families to take action, but after the first phase of grave removal there remained about two thousand unclaimed remains.[23] In April 1948, way beyond the set deadline, the association informed its members that it would start removing the unclaimed remains to the Guang-Zhao Cemetery (Guangzhao shanzhuang) in Dachang. The Lingnan Cemetery took care of the removal of graves for the families at a cost of 10 million yuan.[24] Yet there were still 651 bone boxes, which remained untouched until 1950.[25] The People’s Government returned to this issue as part of its policy to rid the city of burial grounds. The Lingnan Cemetery was targeted as one place the authorities were eager to turn into a production site. In September 1950, the administrative board received an offer by a private entrepreneur to establish a leather factory, but the cemetery still held ossuaries that needed to be removed. The Lingnan Cemetery gave families two months to retrieve them, after which the rest would be buried in the Guang-Zhao Cemetery.[26]

Despite the pressure on the Lingnan Cemetery, there was no systematic policy to force the removal of graves from old cemeteries in the postwar period. It may be that the municipal government had more leeway with the Lingnan Cemetery due to the lack of a proper land title.[27] Or was it simply that its status as a burial ground owned by powerful native-place associations generated a long trail of correspondence? There were many cemeteries in the urban districts that the municipal authorities chose to overlook. The main policy was to designate three areas (Dachang, Pusong, and Pudong) where cemeteries could open. When the Pudong-based Xi’an Cemetery sent its registration form in December 1948, the Bureau of Public Health was hesitant about issuing a license since the cemetery was not located in one of the designated zones. To back up its application, the Xi’an Cemetery produced its original registration, issued in 1936 by the Shanghai Municipal Government.[28] We can assume that denying the registration would not change the situation, while the legal ground for a forced evacuation, short of condemning the land, was not clear.

Self-Regulation

The major threat to cemeteries, however, was less the decisions made by the municipal administrations than the very process of urbanization and densification of the population. The charity graveyards were the burial grounds that faced the greatest threat in the competition for land.

Charity graveyards were simple burial ground with a very plain appearance. Most of the time, they were just an open space made up of small tumuli, the most common form of graves in the Jiangnan region. Burial often meant very shallow interment and covering the coffin with a mound of earth. In fact, charity graveyards were often no different from the many small graveyards to be found around villages. From reading the press, it appears that graves received a small tombstone, which may have distinguished them from the more anonymous rural graveyards. Yet, because charity graveyards were places where coffins arrived from different sources, burials did not always take place immediately. This was a major source of complaints by local residents who voiced their discontent to the authorities. Was this an issue of flow and a rational choice to store coffins and bury them in batches, or was it the outcome of lax administration or sheer neglect? Practices varied, but what had been acceptable when the burial grounds were in the middle of fields became untenable in an urban context.

Benevolent associations took upon themselves the decision to sell cemetery land when they realized both the impracticality of a burial ground in an urbanized area and the opportunity to invest in income-generating rental housing. In 1912, such a decision stirred up a heated debate within the Tongren Fuyuantang as several members and the Ningbo Guild opposed the sale.[29] Nevertheless, urban expansion was an unending process that challenged the preservation of charity graveyards in the city and forced the benevolent associations to relocate and to raise funds to purchase new cemetery land.[30] In 1925, the construction of roads leading to the new Jiangwan racecourse displaced individual tombs and the Houren Shantang charity graveyard.[31] In December 1932, the Guoyutang realized it had to relocate a cemetery it owned in Rihuigang, previously a rural area south of Zhaojia Creek that had turned into a thriving residential and industrial area. The charity published notices in Shenbao and Xinwenbao to inform families they had a chance to rebury the remains themselves—this confirms graves were individualized and named—and that otherwise the remains would be moved to Guoyutang’s new graveyard in Tangwan in Qingpu.[32]

When cemeteries were established, their initiators did not foresee that the pleasant rural setting they had selected for their burial ground would one day be surrounded by a dense street grid and crowded with shops, houses, and unstoppable traffic. In May 1929, the Shanghai Federation of Actors (Shanghai shi lingjie lianhehui) made public its decision to leave its Liyuan Cemetery on Rue Gaston Kahn in the French Concession and move all the graves to a new site near Zhenru. The cemetery had been established before the 1914 extension of the settlement. The cost remained the responsibility of each grave owner, but the federation offered to help those with little means.[33] The federation decided to build rental houses on its cemetery land.[34] The choice of location for the new cemetery in Zhenru, however, was unfortunate. For a while after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese conflict in 1937, the cemetery was inaccessible from the city.[35]

In January 1934, the Chinese Muslim Cemetery of Rihuigang, south of the French Concession, found itself fully surrounded by factories and houses. The Muslim community decided to purchase land near Zhenru to establish both a regular and a charity cemetery. The opening ceremony, including a procession that started at the mosque on Fuyou Road in the former walled city and proceeded to Zhenru, drew about a thousand people. In this case, however, the graves in the original cemetery were left untouched.[36] The Muslim community faced another challenge when the Japanese army decided to seize the small 1.6-acre (10-mu) cemetery in Zhenru to make space for the construction of a railway line. They opposed the decision and sought to have the railway rerouted to spare their cemetery. Feelings ran very high during an emergency meeting held on October 5, 1939, but the Japanese prevailed.[37] The Tongren Fuyuantang also chose to relocate one of its cemeteries in Rihuigang (south of the French Concession), which it had established in 1903. It removed 1,800 coffins and 1,097 urns.[38] The Shenbao occasionally mentions other cemeteries of the same association in the city about which we know nothing, except that they must have been relocated at some point in time.[39]

The most prominent case of cemetery itinerancy, however, is that of the Guang-Zhao Guild.[40] The Chaozhou Guild and the Guang-Zhao Guild initially established the joint graveyard—Lingnan shanzhuang—in 1847 on 19 mu of land (3 acres) less than a mile outside the West Gate.[41] Although the Lingnan shanzhuang remained open until the 1930s, the Guang-Zhao Guild chose to establish its own graveyard in 1872 on 70 mu (11.5 acres) of land it acquired in the countryside, between Soochow Creek and the future Sinza Road, seemingly far away from the International Settlement. As urbanization progressed, however, the guild started to worry about the extension of the settlement and in anticipation bought a large piece of land (133 mu/22 acres) in 1896 in western Zhabei on the far side of Soochow Creek. The whole Sinza Cemetery was eventually incorporated in the International Settlement after the 1899 extension. The guild gradually transferred the remains of the sojourners to the new location.

By 1920 the ever-increasing Cantonese community produced such a large number of deaths that the graveyard started to fill up. Moreover, the selected location, once a desolate riverbank, had developed into a vibrant neighborhood, Zhabei, adjacent to the graveyard. Once again, the Guang-Zhao Guild had to find a new place. In view of its past experience and the expansion of its community, the guild bought a very large track of land (300 mu or 49 acres) in 1924 between Jiangwan and Dachang. The large cemetery was planned to accommodate ten thousand public (or "model") graves, fifteen thousand paupers’ graves, and eight thousand children’s graves. By 1950, the cemetery covered 538 mu (88.6 acres), with only 11.5 acres of land still unused. By then, it had received forty thousand paupers’ remains and four thousand regular burials. In 1958, the People’s Government started to level the land—there is no information on the fate of interred remains—to build new housing. In 1992, the last vestige of the cemetery, its entrance pailou, was torn down. The whole cemetery is now the site of the Pengpu New Village (Pengpu xincun).[42]

These examples show that there was no lack of movement of funeral artifacts—tombs, graves—and even whole burial grounds in modern Shanghai. We can only partly trace the trail left on the ground by the multiple resting places the benevolent associations or the guilds established in full confidence they would provide a final and permanent resting place for their dead. The excavated remains found their way to new burial grounds located in an ever-increasing radius from the city, nearby villages or town now fully enclosed in the Shanghai urban area. All the cemeteries that opened in the republican era, and even those of the postwar period, in seemingly remote locations, eventually faced the threat of urban sprawl.

Wartime Erasure

War affected cemeteries in many ways, but the most dramatic impact was their forced removal. The Shanghai Cemetery (Shanghai gongmu zanghu qianzang) was the main case during World War II. It was located in the Jiangwan area, where the Japanese army had concentrated both troops and equipment. The Shanghai Cemetery disappeared only seventeen years after its opening. In 1943, the Japanese navy decided to build a new aerodrome. Until then, the Japanese had used the Japanese golf course along the Huangpu River. The Shanghai Cemetery was located in the middle of the area earmarked for the new airfield. The Japan military ordered that all the graves be removed by the end of June 1943 to make room for the planned airfield. It also purchased 40 acres (130 mu) to establish a new cemetery to regroup all the individual tombs scattered in the fields condemned for the construction of the airport. Altogether, about ten thousand were removed from the area.[43]

The municipal government had to find an alternative location to rebury the excavated remains from the Shanghai Cemetery, one of the largest private cemeteries in the city (248 mu).[44] Eventually, the Bureau of Land proposed a private cemetery, the Miaohang Cemetery, which would receive the bulk of all the remains, and the Japanese-run Hengchan Company.[45] The Miaohang Cemetery was entrusted with the actual removal of the remains. The second issue involved logistics. The Shanghai Municipal Government published notifications in the press inviting families to come and collect the remains and have them reburied in Miaohang.[46] Its press announcements pointed out that this was the sole opportunity to remove the remains before forced eviction. The bulk of the cost was to be borne by the powerless families. The municipal government made it plain that coffins “without owners” would be buried together in one place.[47]

Because of Japanese pressure, excavation started almost as soon as the notification was issued. The Bureau of Public Health hired ten coolies to dismantle the buildings and to start excavating the coffins. Coffins were gathered on open ground pending their removal. This created trouble for the municipal government. The people who lived in the vicinity protested against the appalling display of broken coffins. And the citizens whose relatives were buried in the cemetery opposed the decision and the authorities’ haste.[48] A group of eighty-one citizens argued that the removal imposed an added expense on families already under strained circumstances. They contended they had no say in the choice of the cemetery (Miaohang) and criticized the layout of the site for reburial. They also pointed out that two thousand of the six thousand buried coffins would remain “orphan” since the concerned families had left Shanghai. Finally, they opposed the idea of a mass burial for the “orphan” coffins and proposed to establish a private company that would use the registers of the cemetery to identify all the orphan remains and take care of their reburial in Miaohang.[49] The archives contain several letters of protest, one signed by 106 citizens, as well as a letter sent to the Central Executive Committee of the Guomindang in Nanjing.[50] At the end of June, a group of citizens organized an association of the families for the transfer of the Shanghai Cemetery to take care of the removal of the excavated remains.[51]

The removal of all the graves took much longer than planned, despite admonishments by the mayor.[52] Was it because of the passive resistance of citizens who dragged their feet? Was it because of the sheer number involved and the logistical difficulties? Was it out of fear of creating a major disturbance if drastic measures were imposed on citizens who were extremely concerned by the issue of the mortal remains of their forebears? Was it simply because the municipal government had underestimated the cost and time that were necessary? While there is no figure of the number of graves transferred by the families, the staff of the Miaohang Cemetery removed 1,318 orphan remains at a rate of fifty a day. Eventually, these orphan remains were buried individually with their original stone or a tablet when none existed. Their removal was completed by October and the Bureau of Public Health reported that the work was completed at the end of February 1944.[53]

The Postwar Legacy

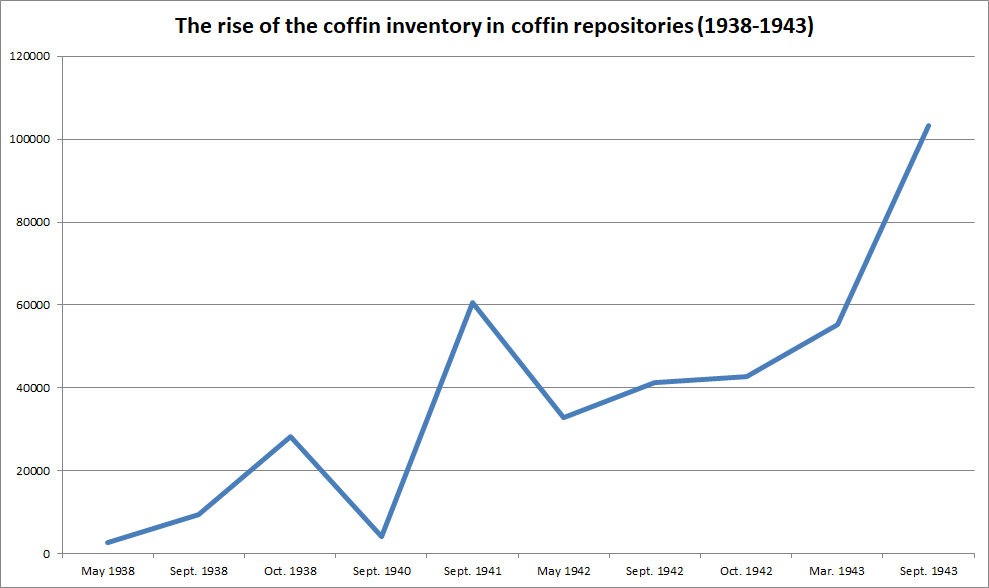

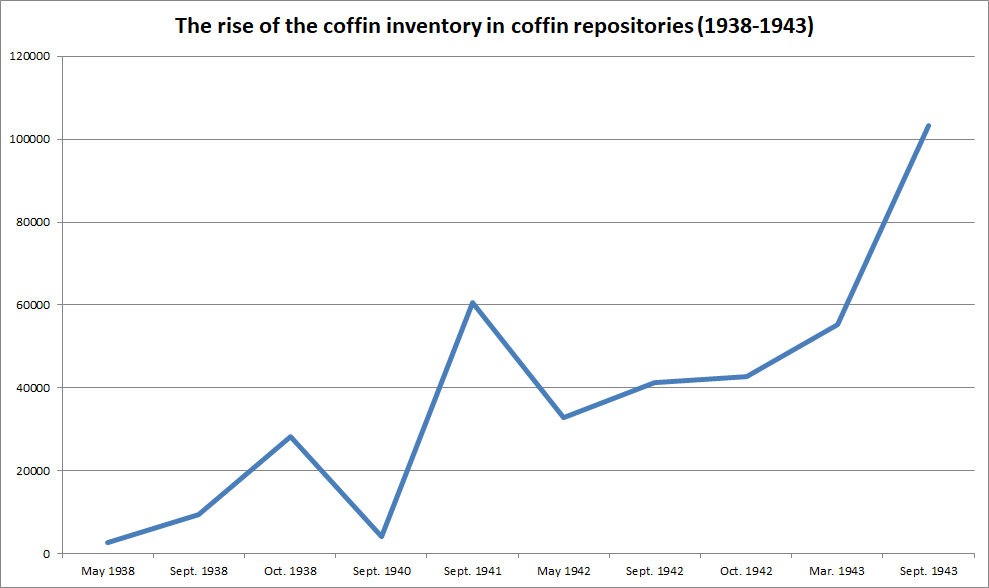

By the end of the war, various sections of Shanghai had literally become “ghost cities.” In these areas, large compounds, sometimes hastily constructed, housed a fast increasing number of coffins. These new coffin repositories were mostly located in the International Settlement, in the Western District, or in the Outside Roads area where the Shanghai Municipal Council had built roads and actually policed the area. Although the Chinese collaborationist municipality claimed jurisdiction over the area, it was considered relatively safe from Japanese involvement and it attracted a considerable number of funeral companies. The area south of the former walled city represented a second major area of concentration of coffin repositories, most of them the property of guilds. The guilds had lost access to their buildings when the Japanese occupied the city. After the Wang Jingwei government established a municipal administration in 1940, the guilds returned to their facilities and progressively, though cautiously, resumed storing coffins (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of stored coffins in the International Settlement

At the end of the war, the total number of coffins stored in the various facilities exceeded a hundred thousand. It was probably closer to a hundred and fifty thousand. The municipal government initiated a policy requiring the removal of all these coffins. Although the guilds and the commercial repositories started shipping coffins, the process was slow and very uneven. A major issue was the loss of contacts—because of death, migration, etc.—with the families of the deceased. The outbreak of conflict between the Nationalists and the Communists again created the same uncertainty as during the Sino-Japanese War. Chinese families became wary of shipping coffins upriver and once again opted for storing them in the city. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) inherited nearly the same inventory of coffins, which it sought to remove from the urban area. While the new authorities wielded more power and clearly pressured the guilds and commercial repositories to cremate all their stored coffins, it took almost three years to rid the city of these coffins. Eventually, only two repositories, located far from the urban area, were allowed to continue.

The stored coffins, however, were not the only challenge the authorities faced at the end of the war. During the first years of the war, the benevolent associations had lost access to their burial grounds in Pudong and in the Jiangwan area. Both came under the control of the Japanese army, especially Jiangwan as discussed above. As an emergency measure, the two major associations involved in the burial of the poor, refugees, and exposed corpses buried the dead on any piece of vacant land they could rent in the Western District of the International Settlement. When fighting moved away from Shanghai, the Shanghai Municipal Council pressured the Shanghai Public Benevolent Cemetery to dig up all the coffins laid down in the temporary burial grounds and remove them from the settlement. Eventually, the council also helped the SPBC gain access to land in the Outside Road area and to rent a large piece of land to serve as a cemetery.

The SPBC used the place to bury the corpses it collected in the streets as well as those from families without means, as it had done before. At the end of 1938, the authorities in the two settlements required the cremation of all the exposed corpses. The SMC never relented on this policy throughout the war. Yet, the SPBC was allowed to continue to bury the coffins of ordinary people. This became the single largest cemetery in Shanghai, with over a hundred thousand coffins laid down, basically above ground, three layers thick. The coffins were covered with no more than a thin layer of earth. At the end of the war, the original owner of the land reclaimed his land, which eventually forced the SPBC, once again, to remove all the coffins, this time to its Puyi Cemetery in Dachang. This ended the era of grave relocation before the CCP took over the city and decided to eliminate all the cemeteries from the urban districts.

The Post-1949 Great Migration

In November 1949, when the CCP turned to the management of death in the city, there were altogether forty-one private cemeteries in and around Shanghai. The People’s Government inherited eight municipal cemeteries with a total of 43,736 graves, with additional space for only 13,539 graves. The main issue the new authorities faced was the lack of burial space to meet the projected need of thirty thousand deaths a year. The Bureau of Public Health and the Bureau of Public Works took over the concept of “cemetery zones” (gongmuqu 公墓區) from the previous administration.[54] No new cemetery and no existing or new repository was allowed to remain in the urban area. The most pressing need was for cemeteries. A total of thirty-eight applications had been received to open new cemeteries, all but five from people who wanted to establish commercial enterprises.[55] To address the need of the population for burial space, the People’s Government settled on permitting the establishment of cemeteries in ten designated areas, each no larger than 10 mu. Like their foreign and Chinese predecessors, the authorities failed to foresee that urbanization would eventually challenge the existence of these cemeteries.[56]

At the same time as it addressed the issue of opening new cemeteries, the People’s Government implemented a policy of systematic removal of the downtown cemeteries. Shanghai was short on open spaces and building space. Under the foreign settlements, all attempts to remove two cemeteries, the Shantung Road Cemetery and the Pootung Sailors’ Cemetery, had failed due to legal objections. The People’s Government was no longer bound by legal considerations, but all the same it had to address the concerns and feelings of the population, not just of foreigners, as many Chinese were buried in these cemeteries. Although the foreign cemeteries were the most obvious targets, because of their location in what had become downtown Shanghai, the same policy applied to Chinese cemeteries. The difference lies in the lack of documentation about their removal, except for the Lingnan Cemetery.

The first cemetery on the priority list of the authorities was the Shantung Road Cemetery. Located in the heart of the city center, four blocks from the Bund and two blocks from Nanking Road, the cemetery had been closed to burials as early as 1871, but the SMC had carefully maintained it throughout the decades. Although very few people could actually relate to the bodies interred there, the Shantung Road Cemetery was a central symbolic landmark in the collective memory of the people of Shanghai.[57] Even after 1945, when the foreign settlements had disappeared, any sign of neglect was resented and could spark a protest. The Chinese municipal government took great care to provide for its upkeep. Work on the relocation of the graves in the Shantung Road Cemetery started in November 1951 with the removal of the 469 remains to the Ji’an Cemetery in the Qingpu District. The Shantung Road Cemetery made way for the Shantung Road Sports Hall (Shandonglu tiyuchang).[58]

The second cemetery that came under the removal policy was the Bubbling Well Cemetery, the second major cemetery the Shanghai Municipal Council opened in 1898. Because it had received burials until 1949—the grave plots had all been sold out before 1943, but burials took place much later—the Bureau of Civil Affairs published press announcements to inform families they had to remove the remains before the end of October 1953 to the Dachang Cemetery. The general policy was to entrust families with the responsibility and cost of the removal, even if the bureau provided staff and vehicles to assist.[59] The removal of the graves was a much larger task as the Bubbling Well Cemetery had received 5,353 burials, of which 371 were the graves of Chinese, even if the official report by the People’s Government noted that only 2,576 were identified.[60] The Bubbling Well Cemetery was turned into a public park (Jing’an gongyuan).

All the cemeteries previously established in the foreign settlements or by the foreign municipal authorities in Chinese-administered territory underwent the same process, although their less central location, except for the Baxianqiao Cemetery, may explain the delay in their removal. The Pahsienjao Cemetery (Baxianqiao), once a burial ground shared by both settlements, including a section reserved for Muslims, was relocated in 1957. The five thousand-plus graves opened since 1863 were transferred to the Ji’an Cemetery in Qingpu. Two years later, the Bureau of Public Utilities proposed to turn the small Lokawei Cemetery (Lujiawan) in the Luwan District into a parking lot. The cemetery had opened in 1908 in Chinese territory, before becoming part of the French Concession after the 1914 extension. There were 2,088 graves, most of which were foreigners (1,994) and only 32 were Chinese. The Office of Funeral Management organized the transfer of the remains to the Ji’an Cemetery.[61]

The other major foreign municipal cemeteries remained in place, even if most were closed to new burials as early as 1949. This was the case of the West Cemetery (Cimetière de l’Ouest) in the French Concession, the last addition (1943) in a string of burial grounds opened to receive the remains of indigents, mostly Russians. This cemetery left no paper trail to document its subsequent fate. The other cemetery for indigents, the Zikawei Cemetery, was entrusted to an automobile factory in 1965, which took charge of removing the graves to an unknown destination. Although we do not know the number of graves, its small size (8 mu) did not allow for more than eight hundred graves. The Hungjao Cemetery (Hongqiao), the largest foreign cemetery in Shanghai, including the Panyu section reserved for Jewish burials, remained in use until 1972. Its subsequent fate is unclear, although it eventually made room for a factory, then a public park. Quite unexpectedly, the unused Pootung Cemetery was left untouched, despite its location in the middle of a busy area on the banks of the Huangpu River. The cemetery was closed to burial in 1904 before it reached its full capacity. The Pootung Cemetery was the last foreign cemetery that remained in the city until its displacement in 1975, with its graves removed to the International Cemetery, one of the most sought-after cemeteries in post-1949 Shanghai, an interesting turn of events for a place clearly marked as a lower-class cemetery.[62]

Aside from the foreign municipal cemeteries, there were a few major places of burial in the city. The oldest ones were a small Parsi cemetery along Fuzhou Road, initially in open land in 1860, but later fully enveloped by houses and hidden behind a row of shops. Few people were aware of its existence in the very heart of the city. It is unclear how long it remained in use, but it was officially closed only in 1952. By this time, the cemetery contained 530 graves. I was not able to document when and where these graves were removed. Jewish cemeteries were the largest burial grounds used by a single community in Shanghai. They lost much of their relevance after 1945 when most of the Jewish population, both former refugees or residents of the foreign settlements, left China. The oldest cemetery (Hebrew Cemetery) operated by Sephardi Jews, opened in 1860 next to the former racecourse on a small plot of land (2 mu) and eventually contained more than three hundred graves. The small cemetery was still there in 1949, even if it had been closed to burials some time at the turn of the century. The Russian Ashkenazi community opened a larger cemetery (20 mu) on Baikal Road, in the remote Yangtzsepoo District in 1922. By the end of the war it had 1,692 graves. It was turned into a public park (Huimin gongyuan) in 1959. Another Jewish cemetery opened during the Sino-Japanese War on Point Road in the Yangtzsepoo District at the easternmost end of the settlement to meet the needs of Jewish refugees. Its 834 graves were removed in the late 1950s, along with all the graves in the other Jewish cemeteries, to the Ji’an Cemetery. The location was turned over a factory. By the late 1950s, foreign cemeteries had all disappeared from the urban districts.

The fate of the Chinese cemeteries is much more difficult to document. There were very few cemeteries in the urban area. The Lingnan cemetery of the Cantonese community had been forced to remove all its graves in 1947 to the Guang-Zhao Cemetery (Guangzhao shanzhuang) in Dachang. All the other cemeteries were located far outside the urban area, at least in 1949. Since the late 1920s, even without stringent regulations by the Chinese municipal authorities, all the commercial cemeteries had opened in the countryside where land was cheap and where the managers could shape the landscape to make the cemetery attractive to Shanghai’s residents. As pointed out above, in the 1940s, the municipality had designated three areas for the opening of cemeteries and rejected all applications that did not conform to this rule. The CCP implemented the same policy, even if it placed restrictions on the size of cemeteries to leave open their removal at a later date. Although no official survey included all the existing cemeteries—surveys usually recorded the active cemeteries, but overlooked the closed ones—there were more than forty active cemeteries around Shanghai in 1949, some with large estates (greater than 100 mu).

The fate of these cemeteries was less conditioned by the pressure of urbanization or administrative decisions than by political frenzy (the Great Leap Forward) or political turmoil (the Cultural Revolution). During the Great Leap Forward, cemeteries like all other units had to prove their worth to the nation and turn their assets to productive use. Where land was available in cemeteries, workers started to cultivate vegetables or raise animals, mostly pigs. Internal official reports documented in great detail the transformation of cemetery land into farms, with record production of carrots or cabbages and hundreds of pigs in straw sheds. Space for burial was restricted to the former alleys or in the space between existing graves. The less important cemeteries were simply leveled and turned into farmland.[63] Throughout the Great Leap Forward, fifty-four thousand graves were said to have been dug up, with no indication about the fate of the remains.[64] There is no evidence that the authorities organized the removal of the graves to other locations. They simply erased the cemeteries from the ground.

The Cultural Revolution brought another onslaught on cemeteries with far deeper consequences. Cemeteries and the rituals families held there became one of the targets of the Red Guards’ attack on the Four Olds (dapo sijiu 大破四舊). In December 1966, gangs of Red Guards literally raided cemeteries to upturn and destroy the tombstones and even dug up coffins and scattered the remains on the ground. Peasants joined the fray, probably under official orders, and desecrated and obliterated around four hundred thousand tombs.[65] The Red Guards even dug up the tomb of the prominent Song family in the International Cemetery. This appalling action gravely distressed Song Qingling, the widow of Sun Yat-sen. Zhou Enlai decided to take action and put a stop to the frenzy. In July 1967, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) placed the cemeteries under its control. By then, nine cemeteries had already been turned over to various work units (factories, hospitals, warehouses).[66] The PLA took over the twenty-four remaining cemeteries.[67] Although the Song family grave was restored, and later turned into the Song Qingling Memorial (Song Qingling lingyuan), the International Cemetery itself disappeared.

Conclusion

The space of death in Shanghai, as embodied by burial grounds and cemeteries, experienced a tremendous change under the combined pressure of population growth, urbanization, administrative regulation, and land prices. Another factor was the emergence of commercial cemeteries that served a different purpose from the burial grounds the guilds and benevolent associations had established to meet the needs of the population. War had also a patent but limited impact, erasing only a few places for the sake of military installations.

The guilds and benevolent associations provided what one could call a service of proximity. Their burial grounds were established next to the city walls, then further away but still at the fringe of the built-up area. As urbanization progressed, the threat of expulsion and displacement became more pronounced with each passing year. Because they were lower-grade burial grounds, with lax management and delayed burials, the charity graveyards were the main targets when local residents voiced their discontent or when an administration needed land for roads or buildings. The graveyards of the long-established guilds fared better because their members were quick to mobilize against any infringement. Yet many guilds chose to relocate when they felt they needed more space for burial.

The commercial cemeteries selected from the start locations that were far from the center of the city. Because they were commercial operations, they took into consideration the cost of land, but also the necessity to have ample open land to design attractive modern cemeteries. Their prospective customers were not the poor and the lower class. They catered to the emerging middle classes who could afford to pay for a decent grave and for their transportation to the cemetery for the annual rites (Qingming, anniversary, etc.). The commercial cemeteries formed a remote belt of burial places all around the city, except Pudong, with a notable concentration in both the northwestern and southwestern corners outside Shanghai.

The removal of graves and complete cemeteries was part and parcel of urban development in Shanghai from the very beginning. Although the relocation of graveyards was a contentious issue, which in a few cases generated rancorous disputes and in exceptional cases rioting, this was mostly a silent process. The historian only gets a glimpse of this erasure through press announcements—they were not systematic— or news about a contested sale of cemetery land. The relocation of most intra-urban Chinese cemeteries was largely undocumented, even if great care was taken to remove each and every mortal remains, down to the last strand of hair.

The Communist authorities actually treated the foreign cemeteries with the same care when they initiated a policy of systematic removal of all cemeteries from the built-up area. How they dealt with the guild and charity graveyards remains a black hole, but the dismantling of the guilds and benevolent associations gave them more leeway on burial grounds shrouded in anonymity. Commercial cemeteries did not represent a challenge per se until the Great Leap Forward when political and economic frenzy turned all such places into production units. Finally, cemeteries as an infrastructure for the management of death came to an end in 1966, when many were destroyed.

The fate of the places that survived the onslaught is unknown. By then, the dead stopped marching around the city.

Notes

Source of image at the top of this essay: Photograph of Pootung Cemetery, Shanghai, 1934. The China Press, March 28, 1934.

[1] Charles B. Maybon and Jean Fredet, Histoire de la Concession française de Changhai (Paris: Librairie Plon, 1929), ii.

[2] Granville G. Loch, The Closing Events of the Campaign in China: The Operations in the Yang-Tze-Kiang and Treaty of Nanking (London: J. Murray, 1843), 44.

[3] See Virtual Shanghai, pictures ID 34479 and ID 34480, https://www.virtualshanghai.net/.

[4] Christian Henriot, Scythe and the City: A Social History of Death in Shanghai (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016), 163 and 171.

[5] Maybon and Fredet, Histoire de la Concession française de Changhai, 286 and 369.

[6] Henriot, Scythe and the City, 80–83; Bryna Goodman, Native Place, City, and Nation Regional Networks and Identities in Shanghai, 1853–1937 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 159–69.

[7] Land Regulations and Bye Laws for the Foreign Settlement of Shanghai, Art. III, Anatol M. Kotenev, Shanghai: Its Mixed Court and Council; Material Relating to the History of the Shanghai Municipal Council and the History, Practice and Statistics of the International Mixed Court : Chinese Modern Law and Shanghai Municipal Land Regulations and Bye-Laws Governing the Life in the Settlement (Shanghai: North-China Daily News & Herald, 1925), 588 and 563.

[8] Chen Li 陈琍, “Jindai Shanghai chengxiang jingguan bianqian (1843–1863): Ji yu daoqi dang’an de shuju chuli yu fenxi 近代上海城乡景观变迁 (1843-1863): 基于道契档案的数据处理与分析” (PhD diss., Fudan University, 2010), 119–20.

[9] Maybon and Fredet, Histoire de la Concession française de Changhai, 237–38.

[10] Ibid., 238.

[11] Henriot, Scythe and the City, 80–83; Goodman, Native Place, City, and Nation Regional Networks, 159–69.

[12] Chen, “Jindai Shanghai chengxiang jingguan bianqian (1843–1863),” 123–27.

[13] Henriot, Scythe and the City, 106–16.

[14] Ibid., 150–51.

[15] Shenbao, March 11, 1926, March 19, 1926, June 12, 1926.

[16] Ibid., January 31, 1874; Bryna Goodman, “The Locality as Microcosm of the Nation? Native Place Networks and Early Urban Nationalism in China,” Modern China 21.4 (1995): 391–94.

[17] Shenbao, March 27, 1873.

[18] Ibid., April 12, 1922, April 25, 1922, May 2, 1922, May 6, 1922, May 8, 1922, May 11, 1922, May 12, 1922, May 13, 1922, June 4, 1922, June 6, 1922, June 10, 1922, June 11, 1922.

[19] “Xinmen wai shenshang qing pu malu,” Shenbao, September 30, 1907; “Ximen wai qian zhong zhulu wenti,” Shenbao, March 26, 1908; “Gongchengju jiejue jiu tiao luxia,” Shenbao, March 26, 1908; “Hu dao duiyu qianzhong zhulu zhi shenzhong,” Shenbao, March 28, 1908.

[20] Shenbao, November 16, 1914, October 12, 1920.

[21] Ibid., April 9, 1915, December 10, 1917.

[22] Letter, Lingnan Cemetery/Guang-Zhao Cemetery/Yanjishantang to members, October 21, 1947, Q117-2-217, Shanghai Municipal Archives (hereafter, SMA).

[23] Report, Cantonese Native-Place Association, September 27, 1950; Letter, Cantonese Native-Place Association, October 23, 1950, Q117-2-217, SMA.

[24] Document, Guangdong Lühu tongxianghui, n.d. [1948], Q117-2-216, SMA. See individual removal authorization forms in Q117-2-217, SMA.

[25] Letter, Guangdong Lühu tongxianghui to members, March 17, 1948; Letter, Guangdong tongxianghui to members, April 4, 1948, Q117-2-216, SMA. Bone boxes were individual ossuaries where the remains were placed after excavating the bones. Several terms were used to designate these boxes: wata, jiuta, and guta.

[26] Letter, Lingnan Cemetery Board to members, September 8, 1950; Minutes, Lingnan Cemetery Board, September 13, 1950; Report, Cantonese Native-Place Association, September 27, 1950, Q117-2-217, SMA.

[27] Henriot, Scythe and the City, 54–55.

[28] Letter, Xi’an Cemetery to Weishengju, December 20, 1948; Memorandum, Weishengju, 1948, Q400-1-3905, SMA.

[29] Shenbao, September 16, 1912, September 20, 1912.

[30] Ibid., December 9, 1903, February 19, 1904.

[31] Ibid., January 13, 1925.

[32] Ibid., December 28, 1932.

[33] “Lingjie lianhehui wei gongmu qianzang shijin yaoqi shi,” Shenbao, May 4, 1929.

[34] “Shanghai shi lingjie lianhehui quanti huiyuan qi shi,” Shenbao, October 20, 1934.

[35] Letter, Shanghai shi lingjie lianhehui, August 9, 1939, U38-5-1485, SMA.

[36] “Zhenru qingzhen di’er bieshu zuori luocheng,” Shenbao, January 24, 1934.

[37] Shenbao, October 3, 1939; “Rifang leqian huijiao gongmu,” Shenbao, October 6, 1939.

[38] Shenbao, December 9, 1903, June 4, 1934.

[39] Ibid., August 3, 1872 (Ximen), August 10, 1879 (behind Siming), April 5, 1896 (Gaochangmiao), April 1, 1899 (Jiang’ansi), April 23, 1900 (Laobeimen), September 13, 1920 (Kansuh Road), October 17, 1920 (Cuiwei’an), November 5, 1931 (Connaught Road), January 11, 1932 (Jumen Road), June 5, 1933 (Chezhan Road), July 4, 1933 (Damuqiao), November 6, 1933 (Panjiaqiao), June 22, 1934 (North Chekiang Road), September 7, 1934 (Bei caixianghuaqiao).

[40] Memorandum, Jingchaju, May 11, 1945, R1-9-361, SMA.

[41] Henriot, Scythe and the City, 54–57.

[42] Zhabei quzhi 闸北区志, section 27 “Minzheng” 第二十八编民政 (Civil affairs), chap. 5 第五章社会行政管理, art. 4, “Binzang” 殡葬 (Funerals).

[43] Letter, Weishengju to mayor, October 24, 1947; Note, Weishengju, October 16, 1947, both in Q400-1-3907, SMA.

[44] Letter, mayor to Japanese navy, April 17, 1943, R1-9-284, SMA.

[45] Letter, TDJ to mayor, April 24, 1943, R1-9-284, SMA.

[46] Letter, Weishengju to mayor, June 19, 1943, R1-9-284, SMA.

[47] Report, Weishengju to mayor, May 11, 1943, R1-9-284, SMA.

[48] Letter, citizens to Weishengju, May 5, 1943, R1-9-284, SMA.

[49] Letter, eighty-one citizens to Weishengju, June 16, 1943, R1-9-284, SMA.

[50] Letter, 106 citizens to mayor, n.d. [June 1943]; Letter, citizens to Guomindang zhongyang zhixing weiyuanhui, n.d. [transferred on June 28, 1943 to the Shanghai mayor]; Letter, citizens to mayor, June 8, 1943; Letter, citizens to mayor, June 14, 1943, R1-9-284, SMA.

[51] Letter, citizens to SZF, June 28, 1943, R1-9-284, SMA.

[52] Letter, mayor to Weishengju, August 26, 1943, R1-9-284, SMA.

[53] Letter, Weishengju to mayor, March 22, 1944, R1-9-284, SMA.

[54] The designated areas varied slightly over time. The municipal government selected four areas labeled bingshequ as early as 1932. It included Jiangwan, Caojing, Pusong, and Yangjing. The postwar administration modified the list, which the People’s Government initially adopted in 1950 with Dachang, Pusong, and Yangsi. In 1952, however, it dropped the last one and added Pudong (Zhangjiazhai). Henriot, Scythe and the City, 117, 184–86.

[55] Report, Weishengju, n.d. [November 1949], B242-1-226, SMA.

[56] Henriot, Scythe and the City, 185.

[57] E. S Elliston, Shantung Road Cemetery, Shanghai, 1846–1868: With Notes about Pootung Seamen’s Cemetery [and] Soldiers’ Cemetery (Shanghai: Millington?, 1946).

[58] Zheng Zu’an, “Shandong lu gongmu de bianqian” [The vicissitudes of the Shandong Road Cemetery], Dang’an yu lishi [Archives and history], no. 6 (2001): 72.

[59] Notification, Minzhengju, October 28, 1953, B1-2-840, SMA.

[60] Letter, Renmin zhengfu waishichu to Waijiaobu, July 21, 1953, B1-2-840, SMA.

[61] Letter, Gongyong shiye guanliju to all concerned units, May 26, 1959; “Shili luwan gongmu qianzang jihua,” May 21, 1959, B257-1-1500, 34, SMA.

[62] Xu Dabiao 徐大標 and Xu Runliang 徐潤良, “Shanghai binzangye yu baoxing binyiguan" 上海殯葬業與寶興殯儀館, Shanghai difang zhi 上海地方誌, no. 3 (1999).

[63] Henriot, Scythe and the City, 189–90.

[64] Shanghai tongzhi 上海通志 (Shanghai gazetteer), vol. 43 Shehui shenghuo 社会生活 (Social life), chap. 7 “Bingzang” 殡葬 (Funerals).

[65] Ibid.,, chap. 17 “Binzang guanli” 殡葬管理 (The management of funerals), art. 2 “Sheshi he fuwu” 設施與服務 (Installations and services).

[66] Henriot, Scythe and the City, 189–91.

[67] Shanghai tongzhi, vol. 43 Shehui shenghuo, chap. 17, art. 2 “Sheshi he fuwu.”